China’s ‘tied aid’ strategy particularly benefits Chinese state-owned enterprises with their loans being backed by African natural resources. As a result, China is not only promoting its state-owned business interests but also deepening their footprint in the region.

By Fabian Herzog

During the Cold War, Russia and the United States (US) used development aid as a politicised measurement of diplomatic relations, especially in Africa to counter each other’s influence.

While the US seems to be retreating from their international engagement by reducing foreign aid globally – and on the African continent- China is pushing its framework consisting of international agreements, loans and development aid to another level. Mixing tools of foreign investment and development China’s programme is incomparable to the projects of other traditional donors.

Traditional Western donors are beginning to recognise the opportunities for business exports to Africa. This is exemplified by Africa’s economic outlook of a middle class of nearly 350 million people, emerging markets and a population in working age bigger than in India and China combined [1].

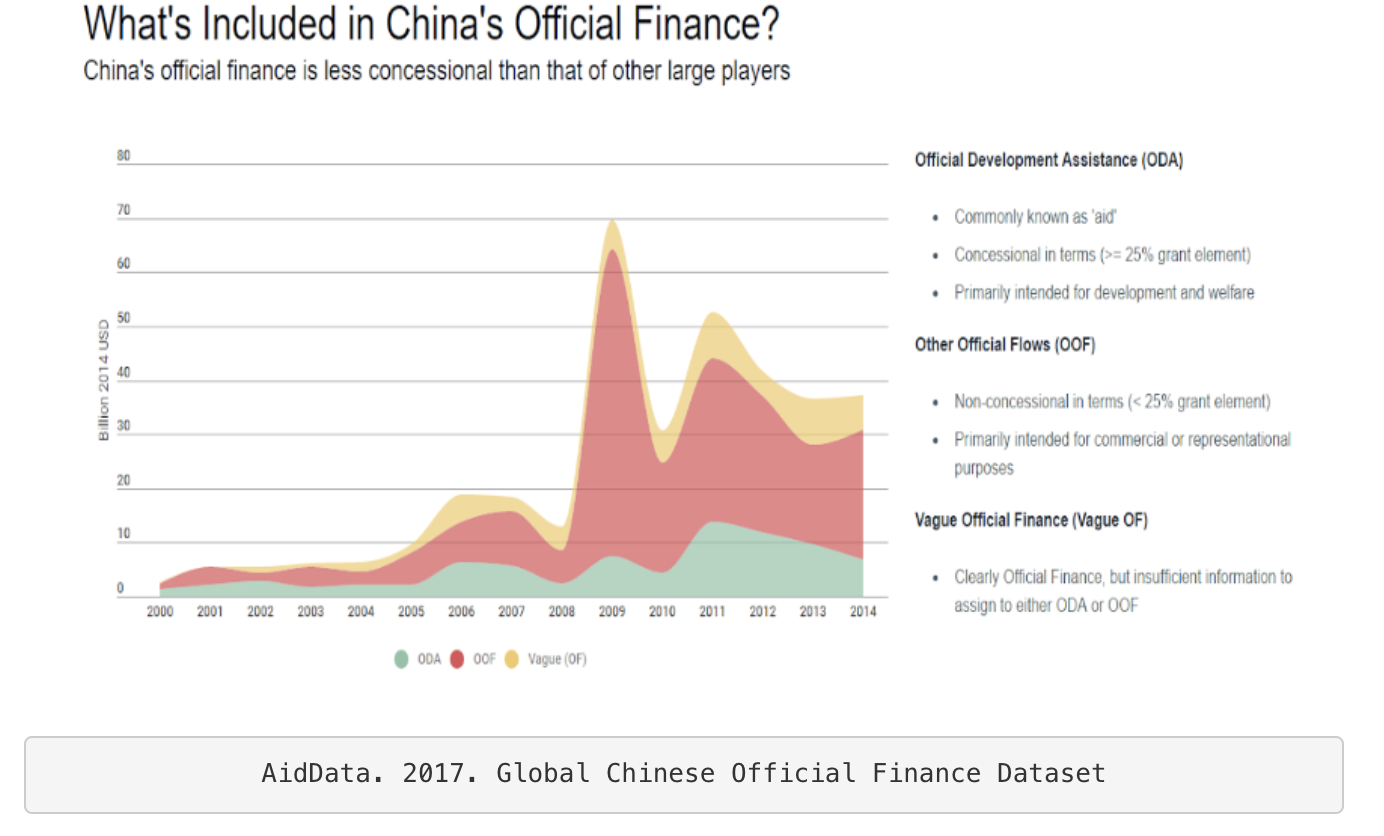

But China has been stepping up their game. The situation has become a competition for the market opportunities in Africa. If China can establish hegemony as the large investor in Africa, it will be the favourite partner for customized solutions in the next decade [2]. The difference between China’s investment projects and traditional donors becomes clear in the following graph. While the American foreign investment consists mostly of Official Development Assistance (ODA), China’s major share of foreign investment is Other Official Flows (OOF) and mainly commercially oriented.

Unlike the democracy promoting approach most Western countries have taken towards Africa, China advocates economic growth through direct investments aiming to provide the country with much needed infrastructural support [3]. The Chinese strategy intends to provide development finance by encouraging Chinese companies and agencies to mix their direct investment, trade, and export. This results in adjusted and customer oriented projects attractive for recipients in Africa but also barely identifiable as aid.

China’s “tied aid” strategy particularly benefits Chinese state-owned enterprises with their loans being backed by African natural resources. As a result, China is financing infrastructure projects in Africa while simultaneously promoting the expansion of its own businesses [4].

Djibouti – The “One Belt, One Road” Initiative – Projecting Strategic Interest

In Djibouti -China’s strategic partner- heavy investment is creating one of the largest free trade zones in Africa, to be used as a gateway into the continent. The military base and port denote a visible Chinese presence. Moreover, China is financing infrastructure projects that will connect Djibouti and Ethiopia through amenities such as gas and water pipelines as well as interconnected transportation via an electrified train line. Consequently, China is not only promoting its state-owned business interests but also deepening their footprint in the region [5].

While investment in Djibouti seems to be unattractive as it is one of Africa’s smallest countries with few natural resources, the country is of strategic important because of the maritime route; trading ships head to the Red Sea, the Suez Canal, and Europe [6]. Djibouti therefore lies on the Chinese New Silk Road’s maritime route. China uses development aid to construct schools, hospitals and sports facilities without any loans, and at the same time the military footprint grows. Djibouti now hosts the first Chinese military station outside of Asia and officially provides support for the Chinese fleet [7]. By providing stability for the country and region, China simultaneously supports its economic interest and creates a military ‘base camp’ for activities in East-Africa.

Beijing appears to be the number one partner for Africa; it avoids influencing domestic politics in Africa whilst gaining access to Africa’s resources, markets, and political support for China’s agenda at multilateral forums [8].

Djibouti is a hub for international actors from both Europe and Asia because it connects the Arab and African spheres. With several troops stationed on its soil (French, American, Chinese, German and Spanish), Djibouti will be given closer examination in following articles.

Sources:

[1] African Development Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,

United Nations Development Programme [ADB; OECD; UNDP] (2017): African Economic Outlook,

https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/AEO_2017_Report_Full_English.pdf,

in:

CSIS (2018): Is the United States Prepared for China to be Africa’s Main Business Partner?,

https://www.csis.org/analysis/united-states-prepared-china-be-africas-main-business-partner.

[2] Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) 2018: Is the United States Prepared

for China to be Africa’s Main Business Partner?,

https://www.csis.org/analysis/united-states-prepared-china-be-africas-main-business-partner.

[3] International Center for Trade and Development [ICTSD] (2017): China’s Infrastructure

Development Strategy in Africa: Mutual Gain?, Yabin Wu, Xiao Bai,

Short URL: https://goo.gl/D6b4uS

[4] Brookings (2014): China’s Aid to Africa: Monster or Messiah?, by Yun Sun,

https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/chinas-aid-to-africa-monster-or-messiah/,

retreived 12.02.2018.

[5] Spiegel (2018): Geopolitical Laboratory, How Djibouti Became China's Gateway To Africa,

http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/djibouti-is-becoming-gateway-to-africa-for-china-a-1191441.html.

[6] ibid.

[7] ibid.

[8] Brookings (2014): China’s Aid to Africa: Monster or Messiah?, by Yun Sun,

https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/chinas-aid-to-africa-monster-or-messiah/,

retreived 12.02.2018.

Graphs:

AidData. 2017. Global Chinese Official Finance Dataset, Version 1.0. Retrieved from

http://aiddata.org/data/chinese-global-official-finance-dataset.