In the wake of the geopolitical shocks, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) faces notable challenges. This article examines Beijing’s response to security concerns within the BRI framework, with a specific focus on the exploration of Private Security Companies (PSCs) as a viable solution. Highlighting the distinctions between PSCs and Private Military Companies, the article traces the evolution of the legal landscape governing Chinese PSCs, noting a shift towards a change in policy in their favour. Against the backdrop of the BRI’s global expansion, often in regions with precarious security conditions, China’s consideration and deployment of PSCs are explored. Despite challenges and limited combat experience, Chinese PSCs are gaining preference from Chinese companies operating abroad. Recent discussions in Beijing suggest an assertive global posture, hinting at an expanded role for PSCs in safeguarding overseas interests and influencing global politics. The article concludes by emphasising the dynamic significance of this evolving aspect within China’s global engagement.

China's Ascent in the New Space Era: Geopolitics, Technology, and the Quest for Outer Space Supremacy

Ever since humankind succeeded in launching its first satellite into orbit, space has been considered the last frontier. The ideological rivalries of the Cold War led to the birth of the space age, which was aggravated by the clash between the US and the USSR. Today, the rapid economic development of emerging powers such as China, the gradual reduction in the cost of rocket launches, technological sophistication, and public-private collaboration and entrepreneurship are just some of the elements that make the commercialization and exploration of Outer Space one of the most vibrant fields of international activity in the present and future. Although this discipline is vast, this article will be an introduction to the People's Republic of China's activities in Outer Space, encompassing both civilian and military aspects (which are closely related). These aspects, and the activities of the US, Russia, or India, may be touched on in future publications.

Navigating the Waters: Chinese Maritime Expansionism

The South and East China Seas have become highly contested regions due to their strategic importance in international trade and global supply-demand dynamics. In this sense, the increasing Chinese maritime assertiveness in the region aims to safeguard economic development, critical shipping lanes, and uphold territorial claims. This assertiveness clashes directly with the countries conforming to the so-called first island chain, stretching from Japan to the Malay Peninsula, and involves territorial disputes and geopolitical tensions.

The Meltdown: Nuclear Relations in the Arctic

This article assesses the impact of multipolarity on nuclear relations in the Arctic. Due to climate change, geopolitical tension, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, nuclear relations in the Arctic are unstable and present serious security risks that cannot be contended with through the use of classic deterrence theory. Melting polar ice means growing competition for Arctic territory and resources amongst North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) members, the Russian Federation, and China. This is occurring alongside the threat of nuclear warfare, which is considered by all actors to be a matter of deterrence despite it being beyond the bipolar rational choice modelling of deterrence theory.

The Realisation of China as an Emerging Global Power and Its Implications for Security

The existing world order mainly characterized by the triumph of Western liberalism is under threat with the emergence of new global power. The Asian great power, China is rising and ready to challenge the status quo. The United States (US) under Trump’s leadership is retreating from global leadership, while China is attempting to fill the power vacuum. China’s increasing strategic investment in international affairs and its commitment supports the argument that China is up for the challenge and serious about global leadership in playing the ‘responsible power’ role.

On the Contentious Subject of Chinese Investment in Africa

Chinese economic expansion demands energy and natural resources that far exceed domestic supply capabilities, posing a serious threat to the nation’s security. From this, diversified Sino-African energy and resource trade relations have become more than just strategic, but rather, vital for Beijing. It is of no surprise that the literature on the subject of Chinese investment in African nations is polarised and influenced by value judgements regarding China’s role and agenda in the international economy.

China’s Expansion into the South China Sea

“Territorial and jurisdictional rights in the South China Sea are a source of tension and potential conflict between China and other countries in the region. The main point of contention and instability is China’s assertion that it has a historical right to the vast majority of the South China Sea in spite of numerous other countries’ recognised territorial claims. China’s aggressive attitude has created substantial tension not only in the region but also for the rest of the international community.”

China’s influence in Africa: forging a mutually beneficial future

China’s long term policy in the South China Sea

The South China Sea (SCS) is a major regional hotspot that embodies critical strategic importance in the Asia Pacific region […] as the de facto regional hegemon, China’s bold claims over almost the entire sea have triggered maritime standoffs and bilateral disputes with its neighbours, such as the legal fight with the Philippines and several skirmishes with Vietnam. These claims are part of China’s long-term strategic interests in the SCS.

Win-win for China? Using Development aid to project strategic interests

China’s ‘tied aid’ strategy particularly benefits Chinese state-owned enterprises with their loans being backed by African natural resources. As a result, China is not only promoting its state-owned business interests but also deepening their footprint in the region.

By Fabian Herzog

During the Cold War, Russia and the United States (US) used development aid as a politicised measurement of diplomatic relations, especially in Africa to counter each other’s influence.

While the US seems to be retreating from their international engagement by reducing foreign aid globally – and on the African continent- China is pushing its framework consisting of international agreements, loans and development aid to another level. Mixing tools of foreign investment and development China’s programme is incomparable to the projects of other traditional donors.

Traditional Western donors are beginning to recognise the opportunities for business exports to Africa. This is exemplified by Africa’s economic outlook of a middle class of nearly 350 million people, emerging markets and a population in working age bigger than in India and China combined [1].

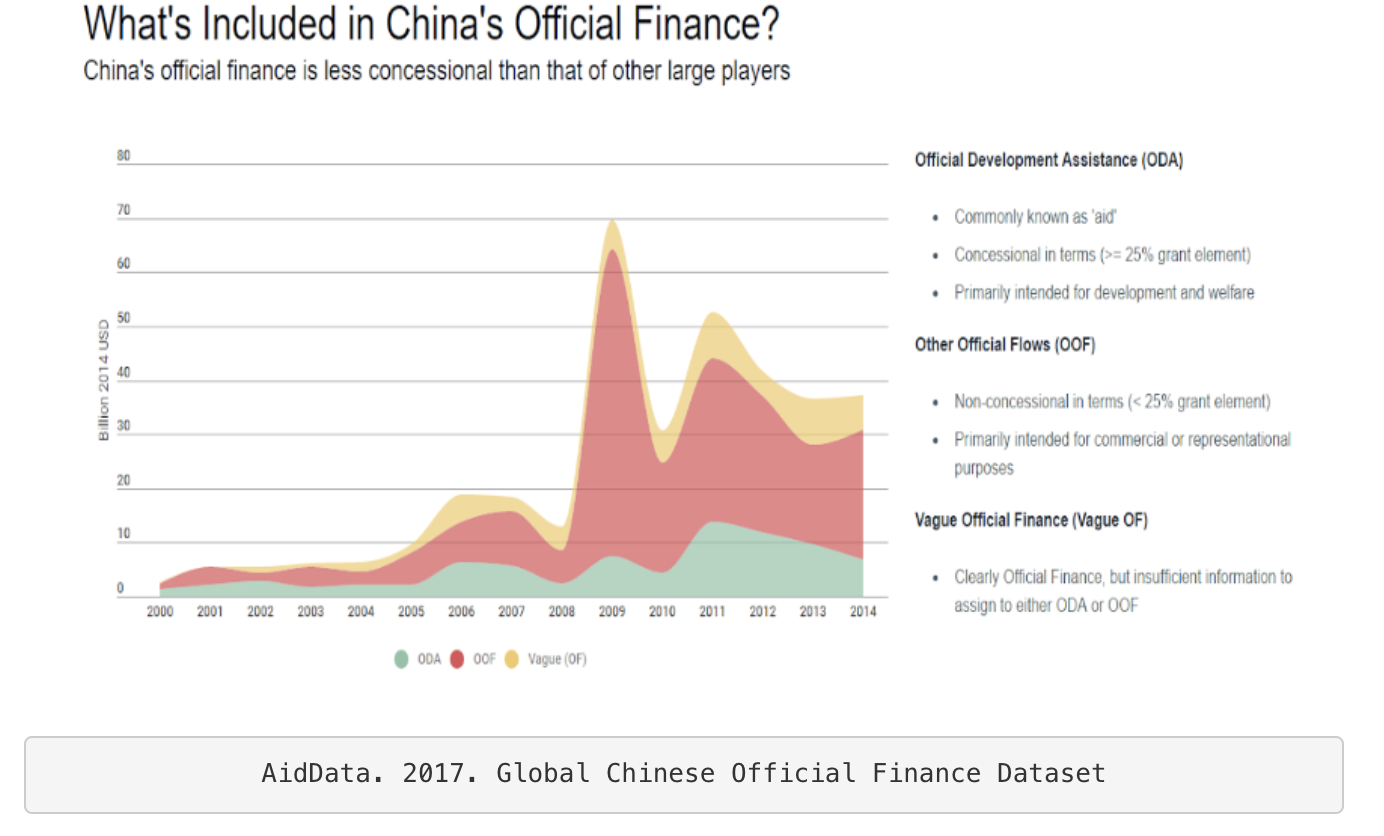

But China has been stepping up their game. The situation has become a competition for the market opportunities in Africa. If China can establish hegemony as the large investor in Africa, it will be the favourite partner for customized solutions in the next decade [2]. The difference between China’s investment projects and traditional donors becomes clear in the following graph. While the American foreign investment consists mostly of Official Development Assistance (ODA), China’s major share of foreign investment is Other Official Flows (OOF) and mainly commercially oriented.

Unlike the democracy promoting approach most Western countries have taken towards Africa, China advocates economic growth through direct investments aiming to provide the country with much needed infrastructural support [3]. The Chinese strategy intends to provide development finance by encouraging Chinese companies and agencies to mix their direct investment, trade, and export. This results in adjusted and customer oriented projects attractive for recipients in Africa but also barely identifiable as aid.

China’s “tied aid” strategy particularly benefits Chinese state-owned enterprises with their loans being backed by African natural resources. As a result, China is financing infrastructure projects in Africa while simultaneously promoting the expansion of its own businesses [4].

Djibouti – The “One Belt, One Road” Initiative – Projecting Strategic Interest

In Djibouti -China’s strategic partner- heavy investment is creating one of the largest free trade zones in Africa, to be used as a gateway into the continent. The military base and port denote a visible Chinese presence. Moreover, China is financing infrastructure projects that will connect Djibouti and Ethiopia through amenities such as gas and water pipelines as well as interconnected transportation via an electrified train line. Consequently, China is not only promoting its state-owned business interests but also deepening their footprint in the region [5].

While investment in Djibouti seems to be unattractive as it is one of Africa’s smallest countries with few natural resources, the country is of strategic important because of the maritime route; trading ships head to the Red Sea, the Suez Canal, and Europe [6]. Djibouti therefore lies on the Chinese New Silk Road’s maritime route. China uses development aid to construct schools, hospitals and sports facilities without any loans, and at the same time the military footprint grows. Djibouti now hosts the first Chinese military station outside of Asia and officially provides support for the Chinese fleet [7]. By providing stability for the country and region, China simultaneously supports its economic interest and creates a military ‘base camp’ for activities in East-Africa.

Beijing appears to be the number one partner for Africa; it avoids influencing domestic politics in Africa whilst gaining access to Africa’s resources, markets, and political support for China’s agenda at multilateral forums [8].

Djibouti is a hub for international actors from both Europe and Asia because it connects the Arab and African spheres. With several troops stationed on its soil (French, American, Chinese, German and Spanish), Djibouti will be given closer examination in following articles.

Sources:

[1] African Development Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,

United Nations Development Programme [ADB; OECD; UNDP] (2017): African Economic Outlook,

https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/AEO_2017_Report_Full_English.pdf,

in:

CSIS (2018): Is the United States Prepared for China to be Africa’s Main Business Partner?,

https://www.csis.org/analysis/united-states-prepared-china-be-africas-main-business-partner.

[2] Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) 2018: Is the United States Prepared

for China to be Africa’s Main Business Partner?,

https://www.csis.org/analysis/united-states-prepared-china-be-africas-main-business-partner.

[3] International Center for Trade and Development [ICTSD] (2017): China’s Infrastructure

Development Strategy in Africa: Mutual Gain?, Yabin Wu, Xiao Bai,

Short URL: https://goo.gl/D6b4uS

[4] Brookings (2014): China’s Aid to Africa: Monster or Messiah?, by Yun Sun,

https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/chinas-aid-to-africa-monster-or-messiah/,

retreived 12.02.2018.

[5] Spiegel (2018): Geopolitical Laboratory, How Djibouti Became China's Gateway To Africa,

http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/djibouti-is-becoming-gateway-to-africa-for-china-a-1191441.html.

[6] ibid.

[7] ibid.

[8] Brookings (2014): China’s Aid to Africa: Monster or Messiah?, by Yun Sun,

https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/chinas-aid-to-africa-monster-or-messiah/,

retreived 12.02.2018.

Graphs:

AidData. 2017. Global Chinese Official Finance Dataset, Version 1.0. Retrieved from

http://aiddata.org/data/chinese-global-official-finance-dataset.