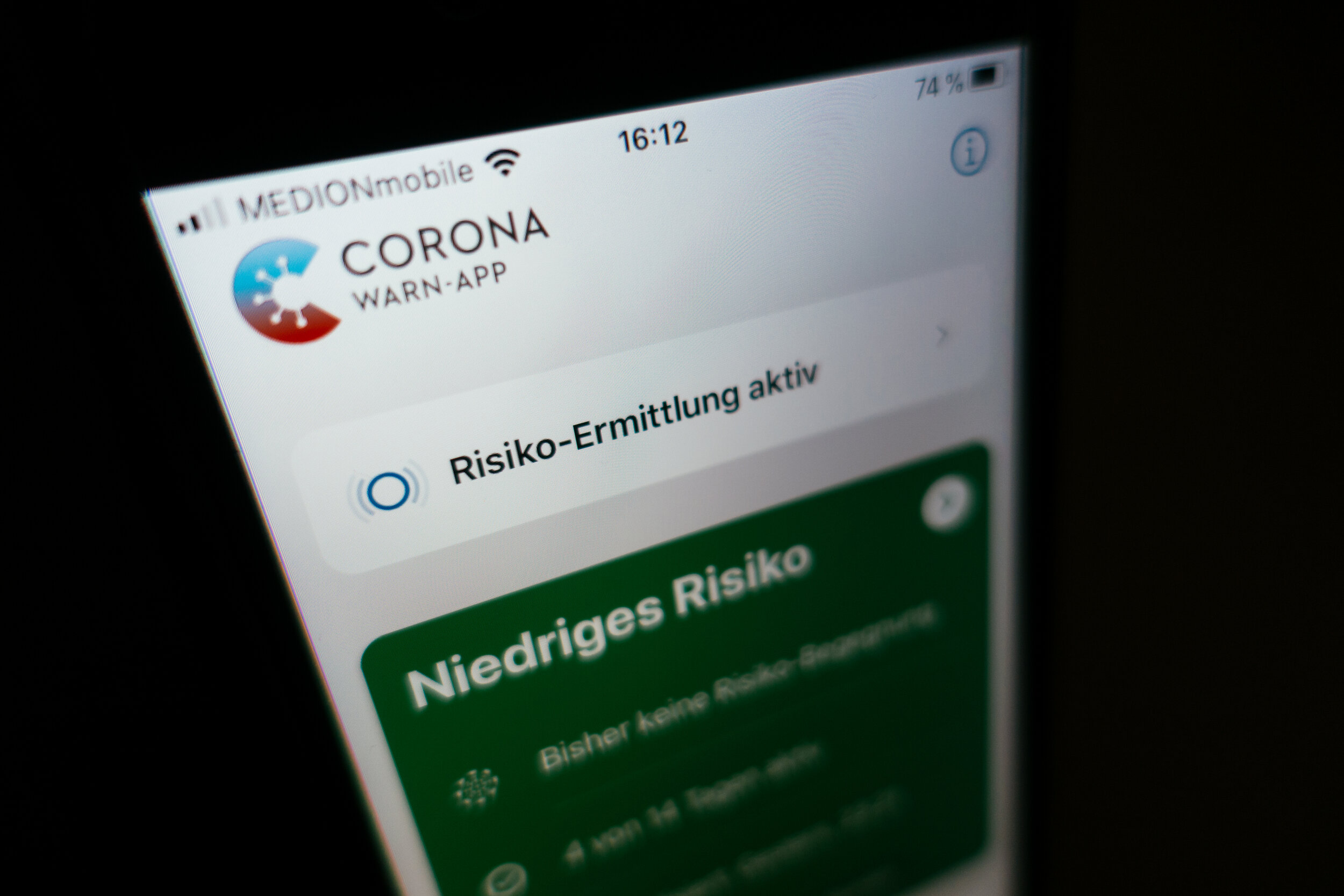

COVID-19 has been disrupting people’s lives and forcing governments to take measures rapidly to contain the virus and prevent further deaths. It took governments by surprise and revealed their lack of preparedness, leading them to formulate policy responses which engaged with securitisation.To fight the pandemic, authorities have introduced measures that drastically infringed upon citizens’ personal freedoms, starting with their freedom of movement. They engaged in a process of securitising COVID-19 using these exceptional times as a rationale to enact exceptional measures. A glaring example is the introduction of contact tracing apps: for citizens to be able to move around freely again, governments had to find a way to track the virus by identifying contaminated citizens and their contacts. Seen by some as an open door to governments collecting more health data, this measure is questionable in terms of ethics and privacy. This article argues that the introduction of contact tracing apps is the result of a securitisation process that stems from governments’ desire to show that they are taking action and controlling the situation.

By Apolline Rolland

September 16th, 2020

April 9th, 2020

In 2014, the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) published a report on the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA’s) Detainee and Interrogation Program (DIP). The report presents ‘overwhelming’ and ‘incontrovertible’ evidence of torture used against CIA detainees between 2001 and 2009. This, however, should come as no surprise knowing that the CIA’s Enhanced Interrogation Techniques (EITs). Although EITs merely amount to a euphemism for torture, proponents claim that such methods are simply ‘enhancing interrogation’ and crucial to obtain information from uncooperative detainees in order to prevent imminent terror attacks. The following questions thus remain: What is considered torture? and Does torture work?

2nd April, 20

Suppose you have a terrorist in custody who planted a bomb in your city, set to detonate in twenty-four hours. There will be disastrous consequences, killing thousands of innocent people, unless you find the location of the bomb. Should it be morally permissible for you to torture the terrorist in order to obtain the needed information?

By Jacopo Grande

March 27th, 2020

Strategy-making is a process that encompasses a wide range of interdependent variables, from cultural to technological factors. It reflects the way a polity imagines itself and its opponents. It is true that historical contexts are unique; thus, Strategies have varied – in terms of objectives, means, and enemies. Nonetheless, it is worth investigating if immutable tenets shape the Strategy function. Indeed, this inquiry constitutes an insightful analysis to unveil patterns in the way societies, given limited resources, think and use force for political aims. The cases of early theories of air power, the annihilation logics of Germany’s colonial policy in Southwest Africa, and US drone warfare against terrorists provide rich observations to test the existence of recurrent features in Strategy.

February 26th, 2020

Although inequality is one of Brazil’s most pressing matters, as a source for violence and instability, it has never been truly securitised. In contrast, Brazil did consider the issue of drug trafficking at its borders to be an existential threat that required the mobilisation of scarce resources and extraordinary measures. This security issue recently reached the phase of de-securitisation, not as a result of its success, but because of financial and political pressures. It was simply too costly and not feasible to protect the roughly 17,000 kilometres of remote land, water, and air that separate the country from Bolivia, Peru and Colombia, South America’s coca sources, and Paraguay, the continent’s main producer of marijuana.

February 19th, 2020

Migration, defined as ‘the process of people travelling to a new place to live’, has always been a common feature of human societies. But, while migrations have significantly enriched European societies in the era of mass movement, a shift seems to have occurred in our understanding of national borders. How did public opinion in the European Union suddenly start to feel threatened by such an ordinary, non-violent phenomenon? Does this reaction result from existing risks, or does it simply reflect the exacerbation of nationalism by a securitisation process?

February14th, 2020

By Emma Hurlbert

The circumstances of refugees in Kenya are defined by the protracted crises in neighboring countries. The ongoing Somali Civil War, conflict in South Sudan, the Rwandan Genocide, the Congo Wars, and violence in eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo have caused hundreds of thousands of people to flee to Kenya. As of May 2019, the refugee population in Kenya is estimated at 476,695 people, the majority of whom are housed in Dadaab Refugee Complex close to the border with Somalia, and Kakuma Refugee Settlement close to South Sudan.

While previous publications by the Security Distillery have provided a general outline and definition of securitization, this article will attempt to contextualize the concept by examining the the fallout of a Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) case centered around the legality of sex work in the country. This article examines the subsequent securitizing response implemented by the Canadian government, in an attempt to abide by the SCCs ruling. Though this is not a traditionally securitized topic, it abides by the general principles of securitization theory in that it helps us to understand why and how securitization happens, and the effects of this decision upon those whom it targets.

By Ethan Pate

February 5th, 2020

WELCOME TO THE SECURITY DISTILLERY 3.0

Securitisation theory

By Maria Patricia Bejarano

January 29th, 2020

We have chosen to organize our articles by theme, in order to add some continuity to the reader’s experience. Our first theme of the Security Distillery this year is to be case studies of securitisation, as this theory aims to answer the core questions by subverting traditional security studies assumptions, and arguing that security issues are socially constructed and not universally given. This entry will be a short introduction to the theory, and case studies in the next month will delve in to applications of the theory, looking at the securitisation of sex work, refugees, immigration and the case of Brazil.

Emergency Management as a Security Discipline

Emergency Management is a sub-discipline of security relying heavily on planning and co-ordination. Effective emergency management leverages resources during natural disasters and other crises to ensure human security both domestically and internationally. Analysing this field at the United States’ municipal and state-levels allows us to examine the varying command structures and assess how the government ensures its citizenry and critical infrastructure during major incidents.

By Caitlyn Roth and Casey Cannon

December 12th, 2019

By Keir Watt

April 20th, 2019

ETHICS AND HYBRID WAR

Hybrid War is emerging as a new form of warfare which military doctrines are struggling to adjust to. Its combination of conventional and non-conventional threats blur the distinctions between civilian and combatant, and between peace and war. This increasingly complex and ambiguous environment presents operational challenges, but also ethical ones.

CHOOSING THE RIGHT STRATEGY: (COUNTER)INSURGENCY AND (COUNTER)TERRORISM AS COMPETING PARADIGMS

Distinguishing between terrorism and insurgency is becoming increasingly challenging for policy-makers and military planners. Terrorist organisations cannot be disrupted through counter-insurgency techniques and insurgencies are extremely resilient to counter-terrorism strategies. Counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency, although similar in certain respects, identify divergent assumptions and modalities for dealing with terrorism and insurgency.