This piece seeks to analyse the specific intersection of women, terrorism and, media in order to provide an overview of the different ways in which female terrorists are portrayed with relation to their motivations, status, and the societal implication of the representations of their individual and political agency. It focuses on whether the framing of women in politically violent groups (such as ISIS) and who commit acts of political violence challenges gender stereotypes or obscures politically violent women’s participation by portraying them as being victimised or irrational so as to remove their capacity to be active agents and the impact this can have on counter-extremist policies.

“The media fetishizes female terrorists. This contributes to the belief that there is something really unique, something just not right about the women who kill. We make assumptions about what these women think, why they do what they do, and what ultimately motivates them. Women involved in terrorist violence are demonized more than male terrorists… The common assumption is that female terrorists must be even more depressed, crazier, more suicidal, or more psychopathic than their male counterparts.”1

The phenomenon of ‘foreign fighters’ travelling to Iraq and Syria was an issue which the Western media took a particular fascination with, partly due to the unprecedented level of Western Muslims voluntarily choosing to join ISIS. In 2015, international strategic consultancy The Soufan Group reported that up to 31,000 recruits from over 86 countries had travelled to join ISIS forces, with 5000 of these coming from Western states2 and 600 of them being women. In fact, in 2016 it was estimated that 40 percent of all French migrants in ISIS-controlled territory were women.3 Moreover, according to a report on the issue of Westerners joining ISIS by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue on the topic “the profile of this cohort differs from the norm; there are a higher proportion of women, they are younger, and they are less likely to be known to the authorities.”4

Yet despite this great empirical evidence of women’s participation in an armed Islamist struggle, media portrayals of women’s violence is continually treated as unnatural or exceptional. This may arise from the preconceived idea that ‘femininity’ is incompatible with violence as women are traditionally represented in culture as ‘nurturers’, ‘carers’ or ‘peacemakers’, whereas men tend to be viewed as more ‘political’ and ‘violent’. This is a phenomenon that was identified by Elizabeth Gardner who argues:

“journalists thus frame female inclusion in political violence as ‘unnatural’ and worthy of explanation, suggesting that women who relocate from the private sphere to the public sphere of political violence necessitate contextual explanations for their actions.”5

Women, terrorism and the media

In “Mothers, Monsters, Whores: Women’s Violence in Global Politics,” Gentry and Sjoberg argue that there are three different narratives in representations of agency of women participating in political violence – mother, monster, and whore – that ultimately serve to ‘other’ violent women.6 It is significant that they highlight the problematic tendency in both academic and policy-related discussions to explain women’s violence as having different motivations from men’s by arguing that “women who commit violence have been characterized as anything but regular criminals or regular soldiers or regular terrorists; they are captured in storied fantasies which deny women’s agency and reify gender stereotypes and subordination.”7 It is these gender norms, such as masculine traits (bravery and strength) and feminine traits (innocence and fragility) which render women’s violence as being “outside of these ideal-typical understandings of what it means to be a woman.”8 This is potentially due to the perceived anomaly of women taking life as opposed to their traditional role as ‘life-giver’ – indeed the idea of motherhood and politically violent women is discussed in reference to the notion of ‘twisted maternalism’ by Gentry.9

In her discussion of twisted maternalism, Gentry critiques how politically violent women such as Palestinian suicide bombers continued to be objectified and denied agency because their reasons and motivations for engaging in such violent acts is framed in relation to the individual’s marriage, divorce, children or lack thereof and is thus explained in domestic and maternal language. This echoes the pathologisation of women terrorists – that there must be something wrong with a woman’s femininity in order for her to have the capacity to commit a terrorist/violent act. Sjoberg and Gentry specifically argue that the dominant Orientalist narrative in academia, politics, and the media is that the sexually dysfunctional Western woman is violent because she refuses to conform, to please men or in fact revolts against her role as one who ought to please men. Whereas Islamic women are violent because there is something wrong with them that makes them unable to please men.10 This is an important point as typically a Western woman’s decision to join ISIS is seen as an irrational act and it is often assumed that the muhajirat have little autonomy in their decision-making. As outlined by Loken and Zelenz this classifies women’s motivation into two categories: (1) women are motivated by romance or sex, complementing Gentry and Sjoberg’s “erotomania and erotic dysfunction” classification of female violence; (2) women are naive and easily tricked by recruiters who sell an unrealistic portrayal of life in ISIS-controlled territory.11 However on the contrary, the true motivations of women partaking in political violence have been shown to correspond to men’s motivations.

Nacos’ Frames used in media coverage of female terrorists

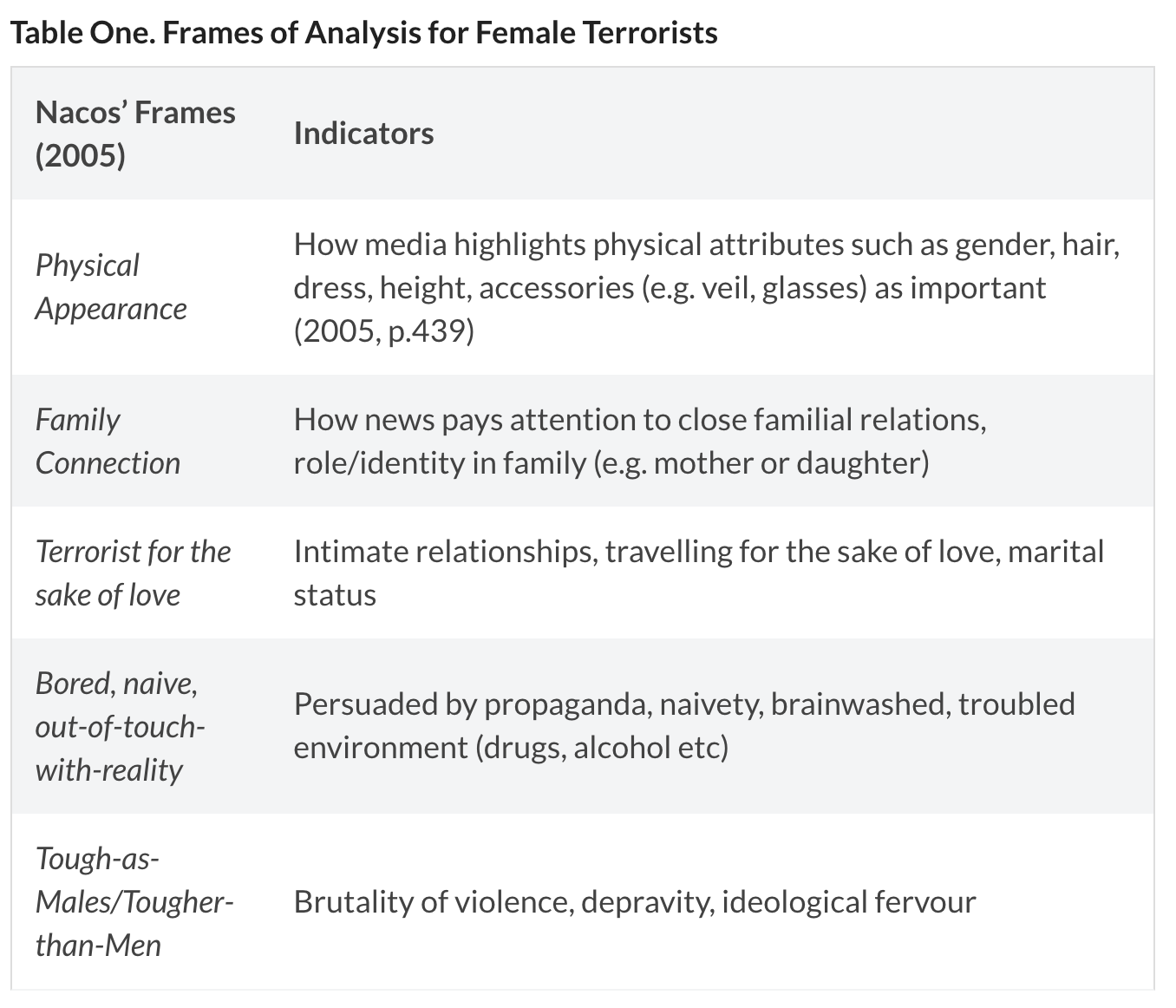

Since female terrorism is generally perceived as exceptional or unconventional, the media often exploits this sensationalism. Yet as emphasised by Nacos there is no evidence that male and female terrorists differ fundamentally with regards to their recruitment, motivations for joining, ideological devotion or even cruelty of their violence.12 Nonetheless despite this, the media representation and portrayal of female terrorists is continually framed by existing gender stereotypes and in fact reinforces them. In this manner, newsrooms are not exempt to the “prejudices that play perniciously just beneath the surface of American life.”13 Therefore these explanatory frames frequently employed by the media are incredibly important as they have the power not only to reveal insights into and shape a society’s understanding of events but also the wider implication of shaping society’s gender assumptions. Regarding the relationship between framing and female terrorists, Nacos specifically researches this relationship between the media and terrorism and in doing so has identified similar gender stereotypes/framing in the media’s representation of female politicians and female terrorists. Table One located below outlines the five frames Nacos identifies as being frequently used in media coverage of female terrorists.

Conclusion

It is important to grapple with the issue of politically violent women, in order to appreciate the media’s role in framing pre-existing assumptions of these transgressive individuals. The media, policy makers, and the general public tend to rely on overly simplistic tropes concerning what female political violence is and how it manifests. The five frames Nacos identifies as being frequently used in media coverage of female terrorists show how the media frequently represents women terrorists in a different way to their male counterparts which does not challenge gender stereotypes. Instead the common frames that portray women often relate to their victimisation or lack of rationality, and in doing so remove their capacity to be active agents. This has large implications in terms of female political motivations and subjectivity as it de-emphasises their political motivations. As such it is imperative that the understandings and assumptions of female terrorists that have already been made are challenged both in the media and in broader discussions – for example the belief that terrorism is a hyper-masculine space composed of predominantly men may become more nuanced when we recognise the role women play.

Finally, it is of the utmost importance to take into consideration the role of women (and gender more broadly) in political violence because if we continue to take seriously only male terrorists then we are bound to miss the gendered consequences of both female terrorism and the impact that representation of female terrorism has, while also continuing to relegate the political agency of women to the background. Most significantly, the unfair prejudices associated with terrorist women may obfuscate the underlying dynamics of recruitment motivations and participation that could ultimately prejudice the efficacy or outcomes of counter-extremist policies.

Sources:

1. Bloom, M. (2011). Bombshell: The Many Faces of Women Terrorists. London: Hurst and Company., pp. 33-34.

2. For the purpose of this essay, ‘Western’ states refers to EU countries, the United States, Canada, Australia or New Zealand.

3. Rubin, A. and Breeden, A. (2016). Women’s Emergence as Terrorists in France Points to Shift in ISIS Gender Roles. [online] Nytimes.com. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/02/world/europe/womens-emergence-as-terrorists-in-france-points-to-shift-in-isis-gender-roles.html

4. Briggs, R. and Silverman, T. (2014). Western Foreign Fighters: Innovations in Responding to the Threat. [online] Isdglobal.org. Available at: https://www.isdglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/ISDJ2784_Western_foreign_fighters_V7_WEB.pdf

5. Gardner, E. (2007). Is There Method to the Madness?. Journalism Studies, 8(6), pp.909-929.

6. Sjoberg, L. and Gentry, C. (2007). Mothers, monsters, whores. London: Zed.

7. ibid, pp. 4-5

8. ibid, pp. 2

9. Gentry, C. (2009). Twisted Maternalism. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 11(2), pp.242.

10. Sjoberg, L. and Gentry, C. (2008). Reduced to Bad Sex: Narratives of Violent Women from the Bible to the War on Terror. International Relations, 22(1), pp.17

11. Loken, M. and Zelenz, A. (2017). Explaining extremism: Western women in Daesh. European Journal of International Security, 3(01), pp.50.

12. Nacos, B. (2005). The Portrayal of Female Terrorists in the Media: Similar Framing Patterns in the News Coverage of Women in Politics and in Terrorism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 28(5), pp.436.

13. ibid pp.437

14. Herlitz, A. (2016). Examining Agency in the News: a content analysis of Swedish media's portrayal of Western women. MA. Utrecht University, the Netherlands., pp.40.