Research shows that terrorists use the Internet to spread their propaganda, communicate, fund their organisations and attacks, train aspiring terrorists and plan and execute attacks off- and online. With the emergence of the metaverse – or Web3 – opportunities will unfold for terrorists online, and so will challenges to tackle these opportunities. Recruitment and attack planning possibilities will likely emerge and new targets might appear. A set of new laws, regulations and capabilities will therefore certainly be needed from stakeholders to ensure users’ safety and prevent the use of the Internet for terrorist purposes.

The Situation in Afghanistan and the Prospects of Peace and Stability in the Region

The article attempts to analyse the situation in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan and its possible implications for the neighbouring countries and global powers. It builds arguments based on the ongoing developments in Afghanistan, challenges faced by the Taliban regime, apprehensions of neighbouring countries and risks for competing global powers. It also highlights that the present scenario has the potential of returning Afghanistan back to the status of a hub of transnational terrorist outfits and becoming a field of competition between rival global powers.

Gender and Terrorism: Women Involved in Terrorism and their Representation in the Media

This piece seeks to analyse the specific intersection of women, terrorism and, media in order to provide an overview of the different ways in which female terrorists are portrayed with relation to their motivations, status, and the societal implication of the representations of their individual and political agency. It focuses on whether the framing of women in politically violent groups (such as ISIS) and who commit acts of political violence challenges gender stereotypes or obscures politically violent women’s participation by portraying them as being victimised or irrational so as to remove their capacity to be active agents and the impact this can have on counter-extremist policies.

“The media fetishizes female terrorists. This contributes to the belief that there is something really unique, something just not right about the women who kill. We make assumptions about what these women think, why they do what they do, and what ultimately motivates them. Women involved in terrorist violence are demonized more than male terrorists… The common assumption is that female terrorists must be even more depressed, crazier, more suicidal, or more psychopathic than their male counterparts.”1

The phenomenon of ‘foreign fighters’ travelling to Iraq and Syria was an issue which the Western media took a particular fascination with, partly due to the unprecedented level of Western Muslims voluntarily choosing to join ISIS. In 2015, international strategic consultancy The Soufan Group reported that up to 31,000 recruits from over 86 countries had travelled to join ISIS forces, with 5000 of these coming from Western states2 and 600 of them being women. In fact, in 2016 it was estimated that 40 percent of all French migrants in ISIS-controlled territory were women.3 Moreover, according to a report on the issue of Westerners joining ISIS by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue on the topic “the profile of this cohort differs from the norm; there are a higher proportion of women, they are younger, and they are less likely to be known to the authorities.”4

Yet despite this great empirical evidence of women’s participation in an armed Islamist struggle, media portrayals of women’s violence is continually treated as unnatural or exceptional. This may arise from the preconceived idea that ‘femininity’ is incompatible with violence as women are traditionally represented in culture as ‘nurturers’, ‘carers’ or ‘peacemakers’, whereas men tend to be viewed as more ‘political’ and ‘violent’. This is a phenomenon that was identified by Elizabeth Gardner who argues:

“journalists thus frame female inclusion in political violence as ‘unnatural’ and worthy of explanation, suggesting that women who relocate from the private sphere to the public sphere of political violence necessitate contextual explanations for their actions.”5

Women, terrorism and the media

In “Mothers, Monsters, Whores: Women’s Violence in Global Politics,” Gentry and Sjoberg argue that there are three different narratives in representations of agency of women participating in political violence – mother, monster, and whore – that ultimately serve to ‘other’ violent women.6 It is significant that they highlight the problematic tendency in both academic and policy-related discussions to explain women’s violence as having different motivations from men’s by arguing that “women who commit violence have been characterized as anything but regular criminals or regular soldiers or regular terrorists; they are captured in storied fantasies which deny women’s agency and reify gender stereotypes and subordination.”7 It is these gender norms, such as masculine traits (bravery and strength) and feminine traits (innocence and fragility) which render women’s violence as being “outside of these ideal-typical understandings of what it means to be a woman.”8 This is potentially due to the perceived anomaly of women taking life as opposed to their traditional role as ‘life-giver’ – indeed the idea of motherhood and politically violent women is discussed in reference to the notion of ‘twisted maternalism’ by Gentry.9

In her discussion of twisted maternalism, Gentry critiques how politically violent women such as Palestinian suicide bombers continued to be objectified and denied agency because their reasons and motivations for engaging in such violent acts is framed in relation to the individual’s marriage, divorce, children or lack thereof and is thus explained in domestic and maternal language. This echoes the pathologisation of women terrorists – that there must be something wrong with a woman’s femininity in order for her to have the capacity to commit a terrorist/violent act. Sjoberg and Gentry specifically argue that the dominant Orientalist narrative in academia, politics, and the media is that the sexually dysfunctional Western woman is violent because she refuses to conform, to please men or in fact revolts against her role as one who ought to please men. Whereas Islamic women are violent because there is something wrong with them that makes them unable to please men.10 This is an important point as typically a Western woman’s decision to join ISIS is seen as an irrational act and it is often assumed that the muhajirat have little autonomy in their decision-making. As outlined by Loken and Zelenz this classifies women’s motivation into two categories: (1) women are motivated by romance or sex, complementing Gentry and Sjoberg’s “erotomania and erotic dysfunction” classification of female violence; (2) women are naive and easily tricked by recruiters who sell an unrealistic portrayal of life in ISIS-controlled territory.11 However on the contrary, the true motivations of women partaking in political violence have been shown to correspond to men’s motivations.

Nacos’ Frames used in media coverage of female terrorists

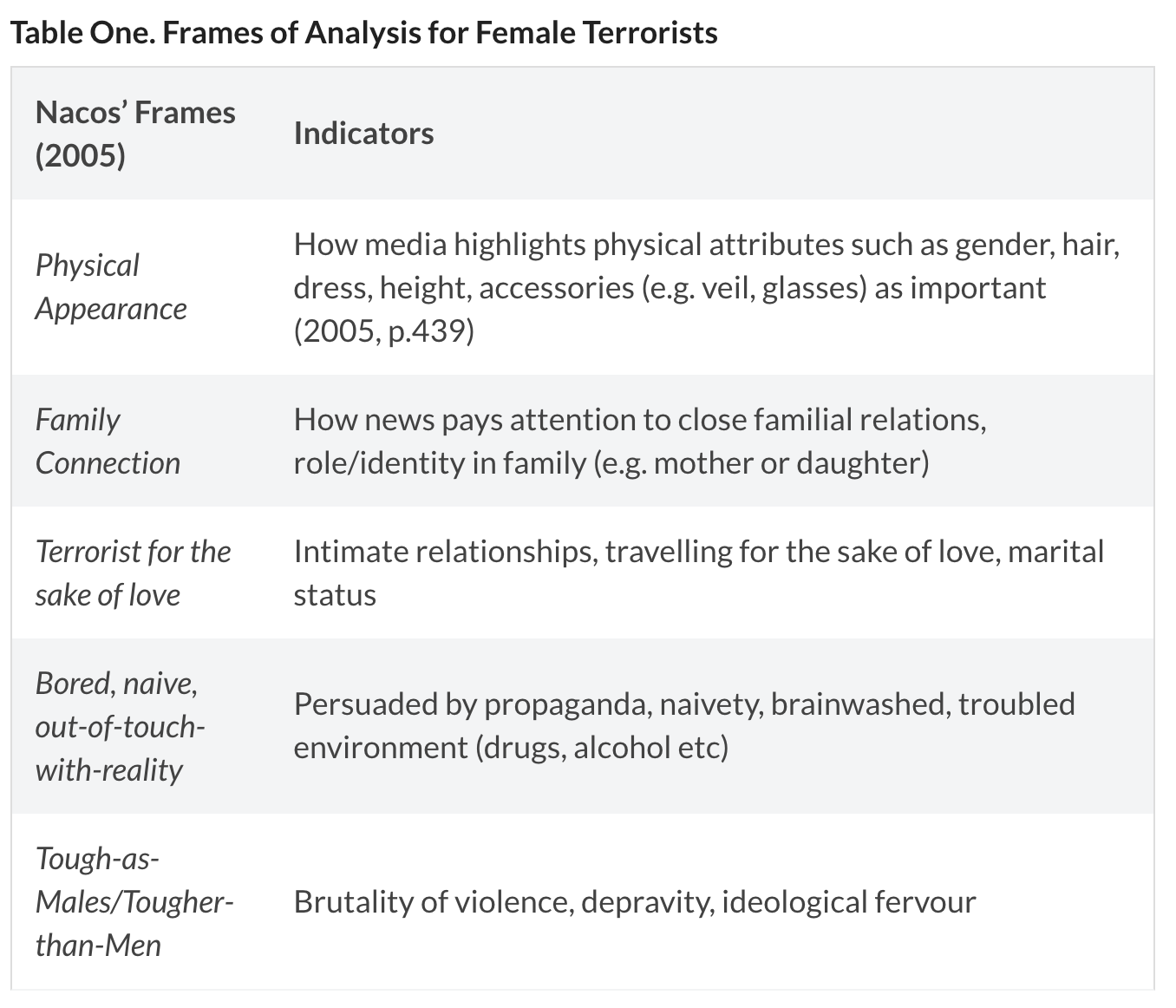

Since female terrorism is generally perceived as exceptional or unconventional, the media often exploits this sensationalism. Yet as emphasised by Nacos there is no evidence that male and female terrorists differ fundamentally with regards to their recruitment, motivations for joining, ideological devotion or even cruelty of their violence.12 Nonetheless despite this, the media representation and portrayal of female terrorists is continually framed by existing gender stereotypes and in fact reinforces them. In this manner, newsrooms are not exempt to the “prejudices that play perniciously just beneath the surface of American life.”13 Therefore these explanatory frames frequently employed by the media are incredibly important as they have the power not only to reveal insights into and shape a society’s understanding of events but also the wider implication of shaping society’s gender assumptions. Regarding the relationship between framing and female terrorists, Nacos specifically researches this relationship between the media and terrorism and in doing so has identified similar gender stereotypes/framing in the media’s representation of female politicians and female terrorists. Table One located below outlines the five frames Nacos identifies as being frequently used in media coverage of female terrorists.

Conclusion

It is important to grapple with the issue of politically violent women, in order to appreciate the media’s role in framing pre-existing assumptions of these transgressive individuals. The media, policy makers, and the general public tend to rely on overly simplistic tropes concerning what female political violence is and how it manifests. The five frames Nacos identifies as being frequently used in media coverage of female terrorists show how the media frequently represents women terrorists in a different way to their male counterparts which does not challenge gender stereotypes. Instead the common frames that portray women often relate to their victimisation or lack of rationality, and in doing so remove their capacity to be active agents. This has large implications in terms of female political motivations and subjectivity as it de-emphasises their political motivations. As such it is imperative that the understandings and assumptions of female terrorists that have already been made are challenged both in the media and in broader discussions – for example the belief that terrorism is a hyper-masculine space composed of predominantly men may become more nuanced when we recognise the role women play.

Finally, it is of the utmost importance to take into consideration the role of women (and gender more broadly) in political violence because if we continue to take seriously only male terrorists then we are bound to miss the gendered consequences of both female terrorism and the impact that representation of female terrorism has, while also continuing to relegate the political agency of women to the background. Most significantly, the unfair prejudices associated with terrorist women may obfuscate the underlying dynamics of recruitment motivations and participation that could ultimately prejudice the efficacy or outcomes of counter-extremist policies.

Sources:

1. Bloom, M. (2011). Bombshell: The Many Faces of Women Terrorists. London: Hurst and Company., pp. 33-34.

2. For the purpose of this essay, ‘Western’ states refers to EU countries, the United States, Canada, Australia or New Zealand.

3. Rubin, A. and Breeden, A. (2016). Women’s Emergence as Terrorists in France Points to Shift in ISIS Gender Roles. [online] Nytimes.com. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/02/world/europe/womens-emergence-as-terrorists-in-france-points-to-shift-in-isis-gender-roles.html

4. Briggs, R. and Silverman, T. (2014). Western Foreign Fighters: Innovations in Responding to the Threat. [online] Isdglobal.org. Available at: https://www.isdglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/ISDJ2784_Western_foreign_fighters_V7_WEB.pdf

5. Gardner, E. (2007). Is There Method to the Madness?. Journalism Studies, 8(6), pp.909-929.

6. Sjoberg, L. and Gentry, C. (2007). Mothers, monsters, whores. London: Zed.

7. ibid, pp. 4-5

8. ibid, pp. 2

9. Gentry, C. (2009). Twisted Maternalism. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 11(2), pp.242.

10. Sjoberg, L. and Gentry, C. (2008). Reduced to Bad Sex: Narratives of Violent Women from the Bible to the War on Terror. International Relations, 22(1), pp.17

11. Loken, M. and Zelenz, A. (2017). Explaining extremism: Western women in Daesh. European Journal of International Security, 3(01), pp.50.

12. Nacos, B. (2005). The Portrayal of Female Terrorists in the Media: Similar Framing Patterns in the News Coverage of Women in Politics and in Terrorism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 28(5), pp.436.

13. ibid pp.437

14. Herlitz, A. (2016). Examining Agency in the News: a content analysis of Swedish media's portrayal of Western women. MA. Utrecht University, the Netherlands., pp.40.

Choosing the Right Strategy: (Counter)Insurgency and (Counter)Terrorism as Competing Paradigms

Distinguishing between terrorism and insurgency is becoming increasingly challenging for policy-makers and military planners. Terrorist organisations cannot be disrupted through counter-insurgency techniques and insurgencies are extremely resilient to counter-terrorism strategies. Counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency, although similar in certain respects, identify divergent assumptions and modalities for dealing with terrorism and insurgency.

Distinguishing between terrorism and insurgency presents significant challenges that policy-makers and military officials need to face. Often, these threats are so interwoven that policy-makers, unable to separate the two, confront them by implementing similar strategies. However, confusion leads to counterproductive outcomes and, instead of containing and reducing threats, misguided measures have the potential to exacerbate the impact of political violence. Terrorism and insurgency are two distinct models of violent conflict. Therefore, they must not be confronted with one-size-fits-all approaches[1]. Consequently, understanding the difference between counter-terrorism (CT) and counter-insurgency (COIN) is a precondition for effectively engaging and disrupting terrorist organisations and insurgency movements, and this understanding is underpinned by the idea that ‘counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency are [neither] mutually exclusive’ nor interchangeable[2].

The United States Department of Defence (DoD) in 2014 defined terrorism as ‘the unlawful use of violence or threat of violence, often motivated by religious, political, or other ideological beliefs, to instil fear and coerce governments or societies in pursuit of goals that are usually political’[3]. Although terrorism is a long-lasting feature of political violence, counter-terrorism as a stand-alone strategy was developed during the 1970s and gained substantial importance in the post-9/11 era[4][5]. Before the 1970s, the majority of Western military analysts considered the phenomenon of terrorism mainly as one of the many tactics deployed by insurgency movements, therefore, countermeasures against terrorism were incorporated in COIN strategies. Military planners started to consider terrorism and insurgency as two separate threats when terrorist groups throughout the 70s composed of alienated individuals, such as the Italian Red Brigades and the German Red Army Faction, engaged in a season of attacks without achievable aims or trying to obtain popular support[6]. Hence, CT emerged as a strategy specifically designed to isolate and disrupt terrorist organisations that, deprived of the population’s support, could be promptly detected and neutralised. The DoD defines CT as ‘activities and operations taken to neutralize terrorists, their organizations, and networks in order to render them incapable of using violence to instil fear and coerce governments or societies to achieve their goals’[7].

Unlike the majority of terrorist organisations, insurgent groups consider it paramount to gain legitimacy from the greater population by championing deeper issues and grievances within society. Insurgencies, as defined by COIN scholar David Kilcullen, are ‘organised, protracted politico-military struggles designed to weaken the control and legitimacy of an established government, occupying power, or other political authority while increasing insurgent control’[8]. In other words, insurgencies are long-term conflicts that the insurgent party wages with the intention of overthrowing the government to take its place. The Vietcong’s uprising in South Vietnam against the central government in Saigon (1954-1976) and the Taliban’s attempts to overthrow the Afghan Government and obtain its power throughout the last 18 years are famous examples of protracted insurgencies. Because insurgents rely on their links with the local population for securing their survival and advancing their cause, governments that implement counter-terrorism strategies to engage insurgency movements are unlikely to emerge victorious. Consequently, strategies that rely on military operations designed to capture and kill insurgents without addressing the root causes of the insurgency are often counterproductive. This is because insurgents benefit from being deeply interconnected with local communities and, when the government launches large-scale operations, they can rely on the protection from the local population to melt away and ‘go quiet’[9]. It is thus not rare for governments to implement countermeasures that, without causing significant damages to the insurgents, generate civilian casualties, alienate local communities, and indirectly legitimise the insurgents in the eyes of the population. A clear example is given by Russia’s framing of the nationalist rebellion in Chechnya during the 1990s as a terrorist uprising. Moscow’s failure to understand that insurgency, and not terrorism, was the defining character of the two Chechen Wars led to the implementation of counter-terrorism strategies that turned a contained rebellion into a widespread jihadi insurgency. Russia’s brutal hunt for the alleged “terrorists” in Chechnya caused the death of innocent civilians, alienated local communities and created the perfect breeding ground for radicalisation and protracted violence in the region[10]. Therefore, successful COIN efforts, instead of only seeking to kill insurgents and disrupt their networks, are mainly directed at severing the link between insurgents and local communities (population-centric approaches). This is defined by Kilcullen as ‘a competition with the insurgent for the right and ability to win hearts, minds, and acquiescence of the population’[11].

CT and COIN are neither mutually exclusive nor interchangeable. The two are not mutually exclusive because if properly implemented their joint action can turn out to be highly successful in tackling terrorism and insurgency. Nevertheless, the marriage between CT and COIN is profitable only when the government is facing insurgents that adopt terrorism as one of their strategies. Firstly, population-centric COIN approaches sever the link between insurgents and population. Secondly, once insurgents are alienated from the local communities and lack the protection of the greater population, they become highly vulnerable to CT strategies. This was the case in Iraq during the “Surge” of U.S. troops in 2007. The strategic approach adopted by the U.S. in Iraq can be divided into two phases. Firstly, the massive deployment of U.S. and Iraqi soldiers provided security and support to the local communities. The long-term presence of security forces at the local level prevented the insurgents from controlling key areas and shifted the population’s allegiance from the insurgents to the security forces. Once these COIN techniques were proven successful in isolating the insurgents, U.S. forces launched the second phase of the “Surge”. Special Operations Forces (SOFs) efficiently combined counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency tactics, engaging insurgents and neutralising their networks without inflicting large numbers of civilian casualties[12]. Hence, before implementing CT strategies, the government must first win the population’s support. As previously mentioned, adapting the wrong strategies in such contexts not only inhibits the government’s success, but may also spawn backlashes, inadvertently strengthen the insurgents’ grip over local communities, and protract the conflict.

CT and COIN are not interchangeable either. Terrorist organisations cannot be disrupted through COIN techniques and insurgencies are extremely resilient to CT strategies. Consequently, adopting the wrong strategy often strengthens the hostile movement. COIN strategies are mainly directed at reinforcing the government’s legitimacy and addressing the root causes of the population’s grievances while granting secondary emphasis to capturing and killing insurgents. But when it comes to confronting alienated individuals determined to spread fear among the population, COIN efforts are generally ineffective. In these circumstances governments should implement CT strategies that emphasise military and law enforcement techniques. Conversely, CT strategies adopted in insurgency scenarios alienate the population, creating the perfect breeding ground for radicalisation and political violence, indirectly strengthening the insurgency.

Policy-makers and military officials often confuse insurgency for terrorism and vice versa because the two phenomena share many commonalities. As Kilcullen states, ‘terrorism is a component in almost all insurgencies, and insurgent objectives lie behind almost all non state terrorism’[13]. Although CT and COIN are not interchangeable, in certain contexts their joint action significantly improves the government’s ability to confront insurgents that implement terrorism as a tactic. The main difference between CT and COIN is that, while the former focuses on neutralising terrorists and disrupting their networks, the latter is an approach aimed at first marginalising, rather than destroying, the insurgent movement[14].

Sources:

[1] Younyoo K., Stephen B. (2013) “Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Russia: Contending Paradigms and Current Perspectives,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, Vol 36, No. 11, p. 918.

[2] Ibid., p. 920.

[3] United States Department of Defense (2014) Joint Publication 3-26: Counterterrorism, U.S. Government Printing Office, p. I-5.

[4] Boyle, M. (2010) “Do Counterterrorism and Counterinsurgency Go Together?,” International Affairs, Vol. 36, No. 2, p. 342. & Merari, A. (1993) “Terrorism as a Strategy of Insurgency,” Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol. 5, No. 4, p. 224-238.

[5] See Rinehart, J. (2010) “Counterterrorism and Counterinsurgency,” Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 4, No. 5, p. 34-37. for a cohesive summary of the origins and evolution of counterterrorism.

[6] Kilcullen, D. (2010) Counterinsurgency: Oxford University Press, p. 186

[7] United States Department of Defense (2014) Joint Publication 3-26: Counterterrorism, U.S. Government Printing Office, p. I-5.

[8] Kilcullen, Counterinsurgency, p. 1.

[9] Kilcullen, D (2009) The Accidental Guerrilla: Fighting Small Wars in the Midst of a Big One: Oxford University Press, p. 32.

[10] Younyoo, Blank, p. 919.

[11] Kilcullen, Counterinsurgency, p. 8.

[12] Kilcullen, The Accidental Guerrilla, p. 115-185.

[13] Kilcullen, Counterinsurgency, p. 184.

[14] Pratt, S. (2010, December 21). What is the difference between counterinsurgency and counter-terrorism?. Retrieved from E-International Relations: https://www.e-ir.info/2010/12/21/what-is-the-difference-between-counter-insurgency-and-counter-terrorism/, p. 4.

Forcing the Taliban to the negotiation table?

With the latest show of force at Ghazni, the Taliban proved during their Al-Khandaq Spring Offensive of being capable to launch coordinated and major attacks. While the US military underestimates the importance of Taliban’s control over provincial districts, the Taliban is proving the opposite – using provincial areas to retreat and plan assaults on major cities. After the Eid al-Fitr cease-fire, the Taliban gained leverage for future peace negotiations in a time where Western-allied forces are trying to force the Taliban to the negotiation table and end the almost 17-year-war.

By Fabian Herzog

Ghazni, Afghanistan

After heavy fighting in the eastern Afghan city Ghazni, the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) reclaimed control on Saturday, 11th August 2018. The attack on the provincial capital – 2 hours from Kabul – was launched by 1000 Taliban fighters on Thursday, 9th August, as part of a major offensive to take over provincial cities [1] [2]. The battle is against the backdrop of the recently reached Eid al-Fitr ceasefire between the Afghan government and the Taliban. The confrontation takes place in a time where Western-allied forces are trying to force the Taliban to the negotiation table and end the almost 17-year-war [3] [4].

Despite warnings ongoing for months that Ghazni’s outskirts were being taken over by the Taliban, the central government did not respond [5]. The Taliban fighting force included Pakistanis, Chechens, and Al Qaeda affiliates. Police forces had to fall back to protect basic government facilities such as the Police Headquarters, the Intelligence Headquarter, and the prison [6]. The battle lasted two days and the ANSF losses reached up to 200. Ghazi has now become a hotspot with clashes constantly breaking out killing 100 police officers and soldiers so far [7].

Taking matters into his own hands, the Afghan National Army´s (ANA) Chief of Staff, Lieutenant General Mohammad Sharif Yaftali, went to regain control of the city [8]. ANSF were backed by US advisers and Special Forces to coordinate the two dozen air strikes and ground operations that drove the Taliban fighters out of the embattled city of Ghazni [9]. The Afghan government’s reaction was chaotic. As the ANA was reinforcing the Afghan police in Ghazni, it provided American ammunition to the Afghan police who use Russian weapons systems [10]. With the end of the military assault, a humanitarian crisis continues to unravel with families unable to leave their homes, alongside failing water and food supplies [11]. The Ghazni hospital is overburdened with over 250 dead or wounded – and numbers are rising. Due to the damage to the telecommunication systems and electrical support lines, the exact situation on the ground is hard to grasp.

The Taliban’s Spring Offensive Al-Khandaq has seen breakouts in other Afghan districts as well. The four-part, coordinated offensive aimed to take over territory, establish checkpoints, secure the area with IEDs, and collect taxes along both the Kabul-Kandahar Highway as well as the road from Ghazni City to Gardez [12]. In Faryab province in the north-west of Afghanistan, the ANA lost an outpost where up to 50 soldiers were killed. In the northern Baghlan Province attacks led to the loss of another outpost and 7 policemen and 9 soldiers killed and 3 soldiers captured [13]. In the Ajristan district, the Afghan Commandos lost 100 members from a forward operating base. The Taliban destroyed the base with two vehicle-borne IED, killing numerous soldiers. Some of the Afghan soldiers fled into the mountains and walked two days while being ambushed by the Taliban. The wounded 22 soldiers were rescued and transported with donkeys out of the mountains [14]. Overall the Afghan military, supported by US forces, is superior to the Taliban when it comes to decisive battles such as Ghanzi and the battle for Kunduz City in 2015 and 2016 [17]. However, the Afghan internal political disagreements and its inability to outmanoeuvre insurgents are a crucial problem [18]. This is demonstrated by the high losses of the ANSF and the Taliban´s capabilities to mobilise and undertake coordinated offensives. Special units such as the Afghan commandos are a crucial part of the NATO Operation RESOLUTE SUPPORT´s strategy to bolster Afghan forces. The high losses and the lost base is a discouraging hit for the Western allied forces and might indicate a declining effectiveness [15].

Retreived from liveuamap.com (2018)

Military stalemate and peace talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban

The Taliban offensive contributes to the heated atmosphere shortly before the parliamentary elections in October 2018. Another suicidal attack took place close to the independent election commission in Kabul [16].

While the US military underestimates the importance of Taliban’s control over provincial districts, the Taliban is proving the opposite – using provincial areas for retreat and planning assaults on major cities [19]. This was the same case at the 2015 siege of Kunduz when the city was slowly surrounded by insurgents, taking over the city step-by-step, which took the ANSF two weeks to retake [20].

From a broader perspective, the new US war strategy for Afghanistan published in 2017 foresees a retreat of ANSF from provincial outposts back to the major cities resembling the small footprint approach adopted by the Bush and Obama administrations [21]. As the examples of Kunduz in 2015 and now Ghazni show, this provides ground for the Taliban. Leading to sufficient time and resources to gather strength; there is space for poppy cultivation fields, training camps, and recruitment. The Taliban is trying to take over major provincial cities such as Kunduz, Helmand, Farah, and now Ghazni since the US led forces took a supportive role in 2014 [22].

After the Eid al-Fitr cease-fire the Taliban gained leverage for future peace negotiations as they proved capable to launch coordinated and major offensives [23]. The Afghan government is facing difficulty convincing critics of the peace efforts [24]. A US delegation met with the Taliban on 23rd July in Doha, Qatar; bilateral talks with the Americans have been a Taliban demand for years. The lack of time restrictions on US engagement in Afghanistan is an uncertain factor for the Taliban – which might act as an incentive for them to join negotiations [25]. This bilateral meeting certainly indicates that the US wants a solution to the almost 17 years of war. After the offensive in Ghazni it seems like the Taliban has increased their negotiation weight and sent their message of strength [26].

Sources:

[1] The Defense Post (2018): Taliban and the Afghan government both claim

control over Ghazni city,

https://thedefensepost.com/2018/08/11/afghanistan-taliban-government-control-ghazni/

accessed 13th of August 2018.

[2] The New York Times (2018): Why the Taliban’s Assault on Ghazni Matters for

Afghanistan and the U.S., By Mujib Mashal

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/13/world/asia/why-the-talibans-assault-on-ghazni-matters-for-afghanistan-and-the-us.html?rref=collection%2Fsectioncollection%2Fworld&action=click&contentCollection=world®ion=rank&module=package&version=highlights&contentPlacement=2&pgtype=sectionfront

accessed on 14th of August 2018.

[3] The Defense Post (2018): Taliban and the Afghan government both claim

control over Ghazni city,

https://thedefensepost.com/2018/08/11/afghanistan-taliban-government-control-ghazni/

accessed 13th of August 2018.

[4] The Defense Post (2018): Afghan government asserts ‘complete control’ over

Ghazni after Taliban assault,

https://thedefensepost.com/2018/08/11/afghanistan-government-control-ghazni-taliban/

accessed 13th of August 2018.

[5] The New York Times (2018): Why the Taliban’s Assault on Ghazni Matters for

Afghanistan and the U.S., By Mujib Mashal,

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/13/world/asia/why-the-talibans-assault-on-ghazni-matters-for-afghanistan-and-the-us.html?rref=collection%2Fsectioncollection%2Fworld&action=click&contentCollection=world®ion=rank&module=package&version=highlights&contentPlacement=2&pgtype=sectionfront

accessed on 14th of August 2018.

[6] ibid.

[7] The New York Times (2018): Taliban Kill More Than 200 Afghan Defenders on 4

Fronts: ‘a Catastrophe’

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/12/world/asia/afghanistan-ghazni-taliban.html?action=click&module=In%20Other%20News&pgtype=Homepage&action=click&module=News&pgtype=Homepage

accessed on 13th of August 2018.

[8] FDD´s Long War Journal (2018): Ghazni City remains under assault, despite

RS assurances, By Bill Roggio

https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2018/08/ghazni-city-remains-under-assault-despite-rs-assurances.php

accessed on 13th of August 2018.

[9] Reuter (2018): Afghan special forces sent to bolster threatened city

defenses, by Hamid Shalizi, Rupam Jain

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-attack/afghan-special-forces-sent-to-bolster-threatened-city-defenses-idUSKBN1KY0MY?feedType=RSS&feedName=topNews

accessed on 13th of August 2018.

[10] The New York Times (2018): Taliban Kill More Than 200 Afghan Defenders on

4 Fronts: ‘a Catastrophe’

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/12/world/asia/afghanistan-ghazni-taliban.html?action=click&module=In%20Other%20News&pgtype=Homepage&action=click&module=News&pgtype=Homepage

accessed on 13th of August 2018.

[11] BBC (2018): Afghanistan: Battle-torn Ghazni residents 'can't find food'

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-45168890

accessed on 13th of August 2018.

[12] FDD´s Long War Journal (2018): Ghazni City remains under assault,

despite RS assurances, By Bill Roggio,

https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2018/08/ghazni-city-remains-under-assault-despite-rs-assurances.php

accessed on 13th of August 2018.

[13] The New York Times (2018): Taliban Kill More Than 200 Afghan Defenders on

4 Fronts: ‘a Catastrophe’

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/12/world/asia/afghanistan-ghazni-taliban.html?action=click&module=In%20Other%20News&pgtype=Homepage&action=click&module=News&pgtype=Homepage

accessed on 13th of August 2018.

[14] ibid.

[15] FDD´s Long War Journal (2018): Ghazni City remains under assault,

despite RS assurances, By Bill Roggio

https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2018/08/ghazni-city-remains-under-assault-despite-rs-assurances.php

accessed on 13th of August 2018.

[16] FDD´s Long War Journal (2018): Ghazni City remains under assault,

despite RS assurances, By Bill Roggio

https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2018/08/ghazni-city-remains-under-assault-despite-rs-assurances.php

accessed on 13th of August 2018.

[17] FDD´s Long War Journal (2018): Taliban routs Afghan Commandos while overrunning

remote district in Ghazni, By Bill Roggio

https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2018/08/taliban-routs-afghan-commandos-while-overrunning-remote-district-in-ghazni.php

accessed on 13th of August 2018.

[18] Reuter (2018): Afghan special forces sent to bolster threatened city defenses

by Hamid Shalizi, Rupam Jain

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-attack/afghan-special-forces-sent-to-bolster-threatened-city-defenses-idUSKBN1KY0MY?feedType=RSS&feedName=topNews

accessed on 13th of August 2018.

[19] FDD´s Long War Journal (2018): Ghazni City remains under assault,

despite RS assurances, By Bill Roggio

https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2018/08/ghazni-city-remains-under-assault-despite-rs-assurances.php

accessed on 13th of August 2018.

[20] The New York Times (2018): Why the Taliban’s Assault on Ghazni Matters for

Afghanistan and the U.S., By Mujib Mashal

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/13/world/asia/why-the-talibans-assault-on-ghazni-matters-for-afghanistan-and-the-us.html?rref=collection%2Fsectioncollection%2Fworld&action=click&contentCollection=world®ion=rank&module=package&version=highlights&contentPlacement=2&pgtype=sectionfront

accessed on 14th of August 2018.

[21] The New York Times(2018): Newest U.S. Strategy in Afghanistan Mirrors Past

Plans for Retreat, By Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Helene Cooper,

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/28/world/asia/trump-afghanistan-strategy-retreat.html

accessed on 14th of August 2018.

[22] The Diplomat (2018):The Trump Administration's Terrible Idea for Afghanistan's Security Forces

https://thediplomat.com/2018/08/the-trump-administrations-terrible-idea-for-afghanistans-security-forces/

By Ghulam Farooq Mujaddidi, accessed on 14th of August 2018.

[23] The Washington Post (2018): Taliban blindsides U.S. forces with surprise Afghan offensive

By Carlo Muñoz

https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2018/aug/13/taliban-surprise-offensive-afghanistan-catches-us-/

accessed on 14th of August 2018.

[24] The New York Times (2018): Why the Taliban’s Assault on Ghazni Matters for Afghanistan

and the U.S., By Mujib Mashal

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/13/world/asia/why-the-talibans-assault-on-ghazni-matters-for-afghanistan-and-the-us.html?rref=collection%2Fsectioncollection%2Fworld&action=click&contentCollection=world®ion=rank&module=package&version=highlights&contentPlacement=2&pgtype=sectionfront

accessed on 14th of August 2018.

[25] The Washington Post (2018): Taliban blindsides U.S. forces with surprise Afghan offensive, By Carlo Muñoz

https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2018/aug/13/taliban-surprise-offensive-afghanistan-catches-us-/

accessed on 14th of August 2018.

[26] The Guardian (2018): Taliban hails 'helpful' US talks as boost to Afghan peace process

Memphis Barker and Sami Yousafzai in Islamabad

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/13/taliban-hails-helpful-us-talks-as-boost-to-afghan-peace-process

accessed on 14th of August 2018.