Following the tumult of the Capitol Riot on January 6th, 2021 and the consequent social media ban of former U.S. President Donald J. Trump, debates around Internet governance have regained momentum. This has led to fervent contention on freedom of speech and social medias’ regulatory frameworks of content moderation. A key target of this moderation is extremist groups with a presence on social media, including the alt-right and jihadists. In particular, women of both groups have been playing an important role in the propagation of extremist ideologies online, frequently instrumentalising hyper-femininity to attract new followers. Because normative gender roles are exploited by violent groups, a gender analysis of how women propagate extremist ideologies is essential to effectively respond to online extremism. This article investigates similarities and differences of alt-right and jihadist women’s online presence and the role gender plays in shaping their respective propagandistic and recruitment methods on mainstream social media platforms.

Weaponisation of Female Bodies: Inaccurate Reports of Sexual Violence in the Donbas Conflict

The use of bodies as weapons of war in the Donbas conflict is denied by the Ukrainian government and United Nations official reports, contrasting non-governmental organisation (NGO) documents which report the contrary. This article explores the gap between the survivors' testimonies, as captured by NGO research, and the official reports and questions the reasons for low victim reporting and high perpetrator impunity.

Gender and Terrorism: Women Involved in Terrorism and their Representation in the Media

This piece seeks to analyse the specific intersection of women, terrorism and, media in order to provide an overview of the different ways in which female terrorists are portrayed with relation to their motivations, status, and the societal implication of the representations of their individual and political agency. It focuses on whether the framing of women in politically violent groups (such as ISIS) and who commit acts of political violence challenges gender stereotypes or obscures politically violent women’s participation by portraying them as being victimised or irrational so as to remove their capacity to be active agents and the impact this can have on counter-extremist policies.

“The media fetishizes female terrorists. This contributes to the belief that there is something really unique, something just not right about the women who kill. We make assumptions about what these women think, why they do what they do, and what ultimately motivates them. Women involved in terrorist violence are demonized more than male terrorists… The common assumption is that female terrorists must be even more depressed, crazier, more suicidal, or more psychopathic than their male counterparts.”1

The phenomenon of ‘foreign fighters’ travelling to Iraq and Syria was an issue which the Western media took a particular fascination with, partly due to the unprecedented level of Western Muslims voluntarily choosing to join ISIS. In 2015, international strategic consultancy The Soufan Group reported that up to 31,000 recruits from over 86 countries had travelled to join ISIS forces, with 5000 of these coming from Western states2 and 600 of them being women. In fact, in 2016 it was estimated that 40 percent of all French migrants in ISIS-controlled territory were women.3 Moreover, according to a report on the issue of Westerners joining ISIS by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue on the topic “the profile of this cohort differs from the norm; there are a higher proportion of women, they are younger, and they are less likely to be known to the authorities.”4

Yet despite this great empirical evidence of women’s participation in an armed Islamist struggle, media portrayals of women’s violence is continually treated as unnatural or exceptional. This may arise from the preconceived idea that ‘femininity’ is incompatible with violence as women are traditionally represented in culture as ‘nurturers’, ‘carers’ or ‘peacemakers’, whereas men tend to be viewed as more ‘political’ and ‘violent’. This is a phenomenon that was identified by Elizabeth Gardner who argues:

“journalists thus frame female inclusion in political violence as ‘unnatural’ and worthy of explanation, suggesting that women who relocate from the private sphere to the public sphere of political violence necessitate contextual explanations for their actions.”5

Women, terrorism and the media

In “Mothers, Monsters, Whores: Women’s Violence in Global Politics,” Gentry and Sjoberg argue that there are three different narratives in representations of agency of women participating in political violence – mother, monster, and whore – that ultimately serve to ‘other’ violent women.6 It is significant that they highlight the problematic tendency in both academic and policy-related discussions to explain women’s violence as having different motivations from men’s by arguing that “women who commit violence have been characterized as anything but regular criminals or regular soldiers or regular terrorists; they are captured in storied fantasies which deny women’s agency and reify gender stereotypes and subordination.”7 It is these gender norms, such as masculine traits (bravery and strength) and feminine traits (innocence and fragility) which render women’s violence as being “outside of these ideal-typical understandings of what it means to be a woman.”8 This is potentially due to the perceived anomaly of women taking life as opposed to their traditional role as ‘life-giver’ – indeed the idea of motherhood and politically violent women is discussed in reference to the notion of ‘twisted maternalism’ by Gentry.9

In her discussion of twisted maternalism, Gentry critiques how politically violent women such as Palestinian suicide bombers continued to be objectified and denied agency because their reasons and motivations for engaging in such violent acts is framed in relation to the individual’s marriage, divorce, children or lack thereof and is thus explained in domestic and maternal language. This echoes the pathologisation of women terrorists – that there must be something wrong with a woman’s femininity in order for her to have the capacity to commit a terrorist/violent act. Sjoberg and Gentry specifically argue that the dominant Orientalist narrative in academia, politics, and the media is that the sexually dysfunctional Western woman is violent because she refuses to conform, to please men or in fact revolts against her role as one who ought to please men. Whereas Islamic women are violent because there is something wrong with them that makes them unable to please men.10 This is an important point as typically a Western woman’s decision to join ISIS is seen as an irrational act and it is often assumed that the muhajirat have little autonomy in their decision-making. As outlined by Loken and Zelenz this classifies women’s motivation into two categories: (1) women are motivated by romance or sex, complementing Gentry and Sjoberg’s “erotomania and erotic dysfunction” classification of female violence; (2) women are naive and easily tricked by recruiters who sell an unrealistic portrayal of life in ISIS-controlled territory.11 However on the contrary, the true motivations of women partaking in political violence have been shown to correspond to men’s motivations.

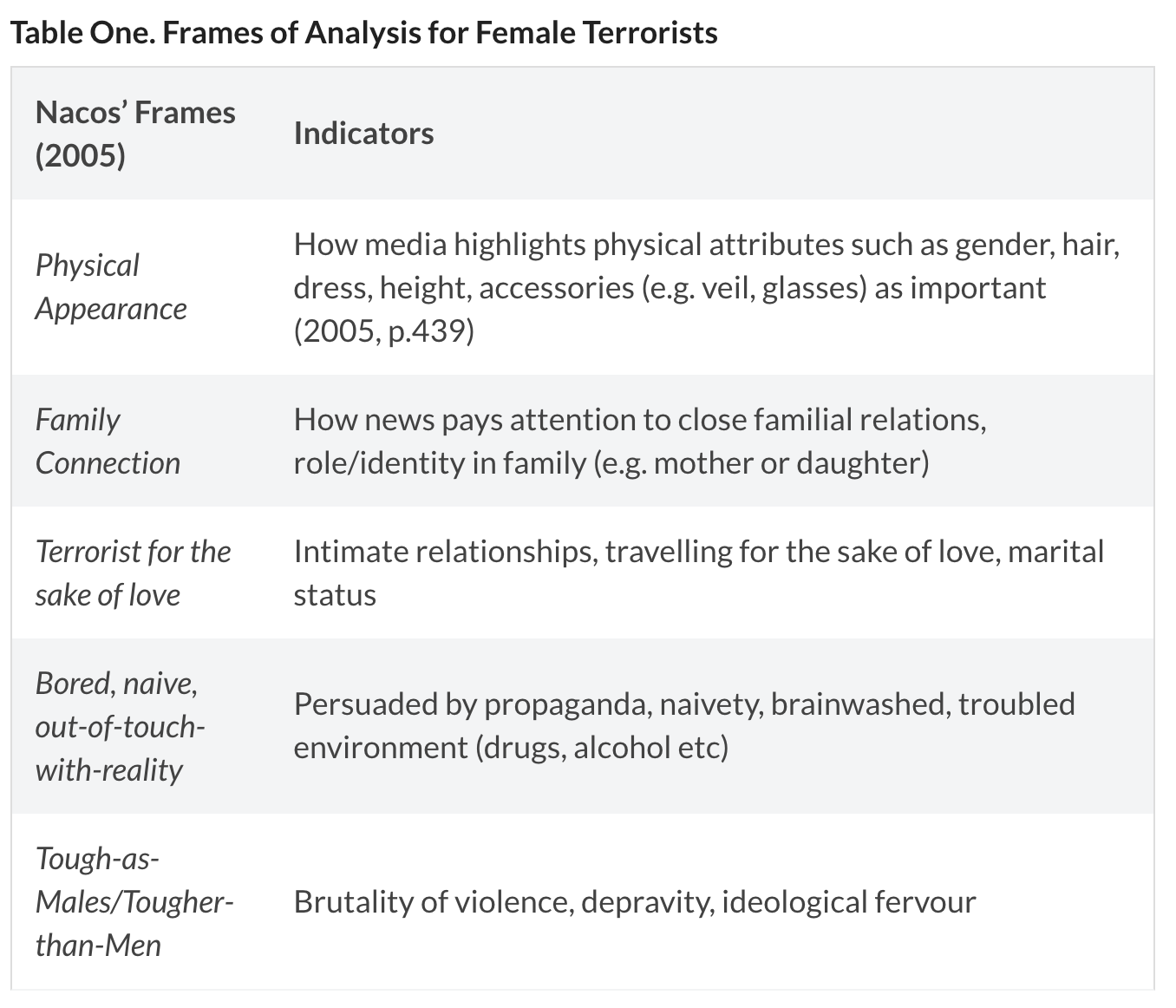

Nacos’ Frames used in media coverage of female terrorists

Since female terrorism is generally perceived as exceptional or unconventional, the media often exploits this sensationalism. Yet as emphasised by Nacos there is no evidence that male and female terrorists differ fundamentally with regards to their recruitment, motivations for joining, ideological devotion or even cruelty of their violence.12 Nonetheless despite this, the media representation and portrayal of female terrorists is continually framed by existing gender stereotypes and in fact reinforces them. In this manner, newsrooms are not exempt to the “prejudices that play perniciously just beneath the surface of American life.”13 Therefore these explanatory frames frequently employed by the media are incredibly important as they have the power not only to reveal insights into and shape a society’s understanding of events but also the wider implication of shaping society’s gender assumptions. Regarding the relationship between framing and female terrorists, Nacos specifically researches this relationship between the media and terrorism and in doing so has identified similar gender stereotypes/framing in the media’s representation of female politicians and female terrorists. Table One located below outlines the five frames Nacos identifies as being frequently used in media coverage of female terrorists.

Conclusion

It is important to grapple with the issue of politically violent women, in order to appreciate the media’s role in framing pre-existing assumptions of these transgressive individuals. The media, policy makers, and the general public tend to rely on overly simplistic tropes concerning what female political violence is and how it manifests. The five frames Nacos identifies as being frequently used in media coverage of female terrorists show how the media frequently represents women terrorists in a different way to their male counterparts which does not challenge gender stereotypes. Instead the common frames that portray women often relate to their victimisation or lack of rationality, and in doing so remove their capacity to be active agents. This has large implications in terms of female political motivations and subjectivity as it de-emphasises their political motivations. As such it is imperative that the understandings and assumptions of female terrorists that have already been made are challenged both in the media and in broader discussions – for example the belief that terrorism is a hyper-masculine space composed of predominantly men may become more nuanced when we recognise the role women play.

Finally, it is of the utmost importance to take into consideration the role of women (and gender more broadly) in political violence because if we continue to take seriously only male terrorists then we are bound to miss the gendered consequences of both female terrorism and the impact that representation of female terrorism has, while also continuing to relegate the political agency of women to the background. Most significantly, the unfair prejudices associated with terrorist women may obfuscate the underlying dynamics of recruitment motivations and participation that could ultimately prejudice the efficacy or outcomes of counter-extremist policies.

Sources:

1. Bloom, M. (2011). Bombshell: The Many Faces of Women Terrorists. London: Hurst and Company., pp. 33-34.

2. For the purpose of this essay, ‘Western’ states refers to EU countries, the United States, Canada, Australia or New Zealand.

3. Rubin, A. and Breeden, A. (2016). Women’s Emergence as Terrorists in France Points to Shift in ISIS Gender Roles. [online] Nytimes.com. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/02/world/europe/womens-emergence-as-terrorists-in-france-points-to-shift-in-isis-gender-roles.html

4. Briggs, R. and Silverman, T. (2014). Western Foreign Fighters: Innovations in Responding to the Threat. [online] Isdglobal.org. Available at: https://www.isdglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/ISDJ2784_Western_foreign_fighters_V7_WEB.pdf

5. Gardner, E. (2007). Is There Method to the Madness?. Journalism Studies, 8(6), pp.909-929.

6. Sjoberg, L. and Gentry, C. (2007). Mothers, monsters, whores. London: Zed.

7. ibid, pp. 4-5

8. ibid, pp. 2

9. Gentry, C. (2009). Twisted Maternalism. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 11(2), pp.242.

10. Sjoberg, L. and Gentry, C. (2008). Reduced to Bad Sex: Narratives of Violent Women from the Bible to the War on Terror. International Relations, 22(1), pp.17

11. Loken, M. and Zelenz, A. (2017). Explaining extremism: Western women in Daesh. European Journal of International Security, 3(01), pp.50.

12. Nacos, B. (2005). The Portrayal of Female Terrorists in the Media: Similar Framing Patterns in the News Coverage of Women in Politics and in Terrorism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 28(5), pp.436.

13. ibid pp.437

14. Herlitz, A. (2016). Examining Agency in the News: a content analysis of Swedish media's portrayal of Western women. MA. Utrecht University, the Netherlands., pp.40.

An introduction to Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs)

The re-emergence of men’s rights activists (MRAs) in social and political contexts in recent years has posed new threats regarding national and international security. Through the utilisation of the internet to further their ideology, develop a community, and radicalise others these threats are increasing. Therefore, in order to understand the legitimacy of the threat posed by MRAs, it is essential to explore their origins.

Groups associated with the far-right have historically held misogynist, anti-feminist, and sexist views and for contemporary far-right groups, this has been no different. However, for many modern-day far-right groups, these values and opinions are no longer a “result of their wider political outlook but rather a central pillar to their ideology” [1]. Nowadays, certain sections of the far-right are heavily driven by anti-feminist ideologies resulting in the emergence and development of male supremacy groups such as ‘Proud Boys’ and ‘Return of Kings’ as extensions of the far-right ideology.

The existence of men’s rights groups in society is nothing new, however, the aims and methods adopted by these groups have changed and evolved over time. As a reaction to second-wave feminism in the 1970s, the ‘men’s liberation’ movement formed in order to provide a critical understanding of the conventions of masculinity [2]. Similarly to the feminist movement the original men’s liberation movement aimed to address the stereotypes and conditions that affected men and masculinity in the social, cultural, and political context. From here the men’s liberation movement split into two factions: those who were pro- and those who were anti-feminist [3]. With each side of this original ideological movement basing their position mainly on the debate surrounding the concept of male privilege and the ways in which male entitlement adversely impacted women globally. Members of the men’s liberation movement who aligned with feminist principles established themselves around topics ranging from male circumcision to child custody. Similarly, this faction also aimed to debate and question the normalised patriarchal standards throughout society deemed detrimental to all genders. This faction supported the idea that gender stereotypes had created harmful circumstances within society for both men and women. However, those affiliated with the anti-feminist approach went on to re-establish themselves as ‘men’s rights activists’ (MRAs). Operating under the belief that “they are victims of oppressive feminism, an ideology which must be overthrown often through violence” [4]. For these individuals gender stereotypes were a positive thing in society and the reduction of them and breaking down of barriers was detrimental to men and masculinity.

Men’s Rights Activists reflect an ideology and global movement which set out to to question and stall women’s gains at all levels [5], believing these gains have been awarded at the expense of men. Sub-groups operating under the same beliefs as MRAs perceive the social, cultural, and political opportunities afforded by the feminist movement as threats to their existence which must be revoked. MRAs hold the belief that feminism, and therefore gender equality, has ‘gone too far’ and in turn harmed men deeply [6]. Certain subgroups such as the ‘Involuntary Celibate’ (incels) who believe sexual relationships are a human right they have been deprived of because of the normalisation of gender equality and global feminism, have called for a ‘gender revolt’ in the hopes of reclaiming a type of manhood rich in “male and white superiority” [7].

As a result of social movements on behalf of women’s rights, anti-racism and LGBTQ+ rights, the power and dominance afforded to ‘white men’ in society are increasingly being challenged [8]. The level of powerlessness felt by these men, particularly those operating within the far-right ideology, is now leading to defensive actions. Contemporary MRAs have utilised the internet in order to develop and spread their ideology whilst also recruiting and radicalising new members. This utilisation has occurred through forums, posting videos explaining their own personal grievances on YouTube, and meme making. Essentially the internet has provided MRAs with a place to evolve their ideology and gain a sense of community and normalisation of their opinions. Yet we are now increasingly witnessing MRAs actions emerging increasingly offline through protests, marches, and extreme acts of violence on areas populated by women. For example the Toronto Van Attack of 2018 when Alek Minassian ploughed a van into crowds of shoppers deliberately targeting women and in turn killing 10 individuals and injuring a further 16.

Fully understanding MRAs and the inclination by some of them to resort to violence in order to achieve their ideological goals is extremely complex. MRAs do not differ from any other extremist groups in that there are specific subgroups and individuals who will feel more inclined than others to turn to violence. To say that all MRAs are inherently violent extremists would simply be wrong, however, as we witness additional attacks inspired by the male supremacy ideology and other non-MRA far-right terrorist attacks referencing male supremacy, the level of threat MRAs and male supremacy pose to national and international security cannot be shied away from by policymakers and law enforcement agencies alike.

Sources:

[1] Murdoch, S. (2018). ‘Societal Misogyny and the Manosphere Understanding the UK Anti-Feminist Movement’ in Lowles, N. (ed), State of Hate 2019: People vs the Elite? (pp. 38-41), London: Hope Not Hate.

[2] Ging, D. (2017). Alphas, Betas, and Incels. Men and Masculinities, pp.1097184X1770640.

[3] Messner, M. A. 2016. “Forks in the Road of Men’s Gender Politics: Men’s Rights vs Feminist Allies.” International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 5:6–20

[4] Zimmerman, Shannon, Lusia Ryan, and David Duriesmith “Who are Incels? Recognising the Violent Extremist Ideology”, Women in International Security (2018) : 1-5 Research Gate

[5] Palmer and Subramaniam, 2018

[6] Allan, J. (2016). Phallic Affect, or Why Men's Rights Activists Have Feelings. Men and Masculinities, 19(1), pp.22-41.

[7] Zimmerman, Shannon, Lusia Ryan, and David Duriesmith “Who are Incels? Recognising the Violent Extremist Ideology”, Women in International Security (2018) : 1-5 Research Gate

[8] Marwick, A and Rebecca Lewis. (2017) Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online. New York: Data & Society Research Institute.

Women’s reproductive health rights and the economic crisis in Venezuela

Venezuela is stuck in a severe economic crisis. Inflation rates are reaching 1,000,000 per cent while GDP is falling by 18 per cent. But the crisis is not simply economic: it has also become a severe health crisis by which women are disproportionately affected. Their fundamental rights to sexual and reproductive health are infringed. As a result, Venezuelan women are forced to take extraordinary measures if they wish to exceed their right to sexual freedom.

By Britta Moormann

The Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela is stuck in a severe economic crisis. The country is experiencing inflation at a rate of 1,000,000 per cent and a falling gross domestic product (GDP) of 18 per cent as determined by the International Monetary Fund (IMF); [1] but the crisis is not simply economic. It has become a severe humanitarian and health crisis by which women are disproportionately affected. Fundamental women’s rights are infringed, primarily their right to sexual and reproductive health and sexual freedom. As a result, Venezuelan women are forced to take extraordinary measures if they wish to exceed their right to sexual freedom.

Sexual and reproductive health is recognized as a decisive pillar of gender equality and empowerment. In 1995, the Beijing Conference established a comprehensive approach to women’s rights. The International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) is considered a consensus document by over 179 states. The ICPD’s document, just like the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, defines equality of men and women with regards to reproductive rights (in its Article 16(1)(e) as ‘the same rights to decide freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children and to have access to the information, education and means to enable them to exercise these rights(.)’[2].

Living a life of sexual freedom includes the positive right to produce new live as well as the negative right not to produce new life to which the accessibility of contraceptives is conditional. In light of the present crisis in Venezuela however, women, as the traditional primary caregivers to their families [3], lack these rights. As a Venezuelan woman very drastically attests in ‘Women of the Venezuelan Chaos’*: ‘Us women always suffer, and for everything. To give birth and to stop giving birth! To stop giving birth! To stop giving birth. My God. Like if we were cows or something.’ [4].

Contemporarily, deciding to give birth as a Venezuelan women means facing potentially life-threatening conditions. Deciding to live out sexual freedom means facing extraordinary economic challenges and health risks. 87 per cent of the Venezuelan households attest to living under conditions of food insecurity, following a mono diet within which man consume 15 different types of food and women consume only 12 different types of food [5]. The extreme food insecurity is exemplified by the fact that 9 out of 10 Venezuelans is unable to pay for its daily nutrients and 6 out of 10 Venezuelans lost around 11 kg during the last year due to the continuous situation of hunger [6].

The majority of families adopted a diet consisting of less diverse food products and a lesser amount of food in general. One family requires at least 51 average salaries to cover basic costs of alimentation [7]. Additionally, the access to and level of medical treatment has worsened strongly. Doctors and medical staff are working under war-like conditions, with 76 percent of hospitals experiencing shortages of medical supplies, of those hospitals among 81 percent lack surgical materials and 70 percent complain of intermittent water supply [8]. Many pregnant women cross the border to Colombia to reach the city of Cucuta to receive medical treatment, as pre-natal check-ups become a rarity in Venezuelan hospitals.

Since 2015, 14,000 Venezuelan patients have received medical treatment in the main hospital of Cucuta. Among the most vulnerable patients are children (suffering from skin diseases, diarrhoea or respiratory problems) and women (mainly due to malnutrition and with only few pre-natal check-ups). The Colombian hospital gives an aspiration of survival to Venezuelan women; a hope of not succumbing to the high maternal mortality rate of 65 per cent [9].

The reality of food shortages persists after child birth. Prices for dairy milk have risen 266,7 percent and the prices of diapers 71,4 percent in 2016 alone [10]. According to UNHCR around 2,3 million Venezuelans have migrated to neighbouring South American countries since 2015, the majority of which are living in irregular situations of non-documentation. Among the main reasons why Venezuelans continue to leave the Republic is the continuing economic and food insecurity, access to medical treatment or essential social services, and physical integrity [11]. Whilst a group of Latin American nations agrees on giving assistance particularly to Venezuelan migrants, Venezuelan President Maduro dismisses migration related figures as incorrect and fights grounds for pre-emptive justification of potential foreign intervention in Venezuelan affairs [12].

By means to secure contraceptives, Venezuelan women face disproportionate economic challenges. The price of condoms escalated to around $169 USD for three condoms on the black market, which equals a five-day salary. Safe sex has become a luxury only a minority of the Venezuelan population is able to afford. Subsequently, a higher number of patients suffer sexually transmitted diseases [14]. Moreover, the fear of getting pregnant is the main reason why more women see an obligation to medical sterilisation or clandestine abortions. In some hospitals, 30 sterilizations a week have been practiced during the course of 2017 to extraordinary cost. Irrespective of the continuing health deterioration, the Venezuelan government perceives its health systems as one of the world’s best. Official health statistics remain unpublished nonetheless [15].

President Maduro denies the reality of a humanitarian crisis politically and continues to follow an antagonistic position towards reproductive health care. Stipends are offered to pregnant women for new born children where maternity culturally is a considerable fate. Contrarily, free sterilization days are offered in public hospitals with rising tendency of patients [16]. Non-governmental organizations criticise the disproportionate risks women take in order to live out their rights to sexual and reproductive health. If both carrying a child and taking measures not to get pregnant is directly linked to taking either disproportionate economic or physical risks, women are exposed to unequal conditions of exercising fundamental human rights.

* A movie portraying the life of five women under the extremity of the Venezuelan crisis, made by filmmaker Margarita Cardenas and presented at the Human Rights Watch’s Film Festival in New York.

Sources:

[1] Friesen, Garth. 2018. “The Path To Hyperinflation: What Happened To Venezuela?”. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/garthfriesen/2018/08/07/the-path-to-hyperinflation-what-happened-to-venezuela/#7bc8884a15e4.

[2] UN. 1998. Rights to Sexual and Reproductive Health – the ICPD Convention and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. [ONLINE] http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/csw/shalev.htm.

[3] Taraciuk Broner, Tamara. 2018. “Mujeres del caos venezolano”. La Vanguardia. https://www.lavanguardia.com/internacional/20180529/443912937067/mujeres-caos-venezolano-venezuela.html.

[4] Marillier, Lou. 2018. “Lacking Birth Control Options, Desperate Venezuelan Women Turn To Sterilization And Illegal Abortion”. The Intercept. https://theintercept.com/2018/06/10/venezuela-crisis-sterilization-women-abortion/.

[5] AVESA, CEPAZ, FREYA, Mujeres en Línea. 2017. Mujeres Al Límite. El peso de la emergencia humanitarian: vulneración de derechos humanos de las mujeres en Venezuela. [ONLINE] https://avesawordpress.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/mujeres-al-limite.pdf, p. 14.

[6] ENCOVI. 2017. Encuesta Nacional de Condiciones de Vida. Venezuela 2017. Alimentactión I. [ONLINE] https://www.ucab.edu.ve/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/ENCOVI-Alimentación-2017.pdf.

[7] Caritas Venezuela. 2018. Monitorio de la Situación Nutricional en Niños menores de 5 años. [ONLINE] http://caritasvenezuela.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/6to-Boletin-SAMAN-Enero-Marzo-2018.pdf.

[8] Watts, Jonathan. 2016. “’Like doctors in a war’: inside Venezuela’s healthcare crisis”. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/19/venezuela-crisis-hospitals-shortages-barcelona-caracas.

[9] Moloney, Anastasia. 2018. “As Venezuela’s health system crumbles, pregnant women flee to Colombia”. Reuters. https://uk.reuters.com/article/colombia-migrants-health/feature-as-venezuelas-health-system-crumbles-pregnant-women-flee-to-colombia-idUKL5N1T34JJ.

[10] AVESA et al., p. 11.

[11] UNHCR. 2018. Venezuela Situation. Fact Sheet. [ONLINE] https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/64428, p. 3.

[12] Valencia, Alexandra. 2018. “Venezuela’s neighbours seek aid to grapple with migration crisis”. Reuters. https://af.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idAFKCN1LK2T0.

[13] UNFPA, The Danish Institute for Human Rights, The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2014. Reproductive Rights are Human Rights. A Handbook for National Human Rights Institutions. [ONLINE] p. 18. https://www.unfpa.org/publications/reproductive-rights-are-human-rights.

[14] Wright, Emily. 2016. “Safe Sex Is a Luxury in Venezuela, Where a Pack of Condoms Costs Nearly $200.” Broadly. https://broadly.vice.com/en_us/article/bmwqy4/safe-sex-is-a-luxury-in-venezuela-where-a-pack-of-condoms-costs-nearly-200.

[15] Ulmer, Alexandra. 2016. “In crisis-hit Venezuela young women seek sterilisation”. Reuters The Wider Image. https://widerimage.reuters.com/story/in-crisis-hit-venezuela-young-women-seek-sterilization.

[16] See Reference 4.