When a rising power threatens to displace an incumbent power, historically the result has been war. The rise of China has triggered heated debate within academia. This question- whether the United States (US) and China will fall into the so-called “Thucydides’ Trap”-is of primary relevance today for policymakers worldwide as both countries intensify their rivalry. Should both countries expand their economic, political, security and cultural cooperation, war is unlikely to be an outcome.

Undocumented Women Domestic Workers in South Africa: An Intersectional Look at Marginalisation and Inequality

Many women from southern African countries migrate without legal documentation to South Africa to seek better economic prospects. However, they often face marginalisation and discrimination in transit and upon arrival. Once they reach their destination there are barriers to their security and stability; namely, the legal code in South Africa hosts a policy gap that exacerbates exploitation by employers. [1] This article centres these women’s experiences as important and deserving of study and protection.

Many undocumented women choose to become live-in domestic workers for South African families, which offers them many benefits, but also costs them greatly. Women are highly concentrated in this sector, with 80% of domestic workers in South Africa being female. [2] The benefits afforded through this arrangement include cash payments and accommodation at the job site, which solves a logistical problem of finding accommodation, but can also provide protection from or mediation with immigration enforcement or police officers. Additionally, in kind payments from employers in the form of clothing, transportation costs, and children’s school fees are commonly received. [3] However, these benefits come at the cost of exploitability and dependence.

Undocumented workers exist on the margins of society, in a legal situation that excludes them, in actuality and out of fear, from accessing their rights. [4] Furthermore, since domestic work is considered to exist within the private sphere and the informal sector, policymakers have failed to create legislative protections regulating the industry. [5] Therefore, undocumented workers in general, and this industry in particular, exist in a policy gap that allows for exploitation by individual employers.

Because they have little legal protection, undocumented workers live precariously and almost entirely dependent on their employers. They report very low wages, which are determined by the employer, long working hours with continuous on call time, and limited personal leave. [6] The constant fear of deportation makes it difficult - if not impossible - for these women to join legally recognised organisations, such as labour unions, which serve to protect the rights of workers and bargain for fair wages. Therefore, it is observed that the lack of collective action among these workers serves to lower the bargaining power of each individual worker. [7] They are replaceable and can easily be dismissed if they do not agree to the employers’ suggested wages or work conditions. [8] Furthermore, live-in status means that these women work for practically all of their waking hours and are often on call for the children when they are asleep. Finally, personal leave for holidays and visits back home are not treated as a right, but are granted at the discretion of the employer, and can be withheld. [9] It should be noted that not all employers exploit undocumented women domestic workers in these ways; however, the choice of an employer not to exploit does not diminish the exploitability or vulnerability of this group. [10]

In 2008 labour protections and rights were extended to all undocumented migrant workers, [11] undoubtedly intended to improve the work situation and increase security for them. Yet many undocumented migrant women still feel as though they have no rights in South Africa and are therefore unable to seek formal and legal support in enforcing their rights, [12] which means that their exploitability and vulnerability have not been ameliorated by the protections. Furthermore, undocumented migrants who are aware of their rights established through United Nations Declarations and South African national law, said they were fearful of reporting rights violations to the police because of the possibility of detention and deportation, which could cost their livelihood. [13]

Intersectionality as a Lens for Understanding Marginalisation

In this section, I discuss the continued low pay faced by undocumented women domestic workers, despite the introduction of laws meant to increase their pay security. I use the theory of intersectionality to understand this phenomenon. In this context, intersectionality refers to the overlapping types of marginalisation faced by these women, including their gender, migrant and illegal status, race, and labour status, which combine to create a complex situation of exploitability and marginalisation. I argue that laws targeting low pay are only marginally effective at increasing equality and empowerment, because they view this issue only as a function of labour rights and fail to address the other aspects of disadvantage that consort to produce persistent low wages.

In actuality, low pay is also a function of status as an illegal migrant, womanhood, and race. [14] It is evident that migrants in general make less money than South African nationals. Undocumented migrants make even less than their documented counterparts because they have little legal redress against unfair wages through the justice system, cluster in low paid jobs, and face discrimination based on their migration status. [15] Undocumented migrant status further contributes to low pay because these women are often not comfortable forming collectives that can bargain on their behalf for better working conditions and remuneration, for fear of deportation. [16] In fact, many women domestic workers from Lesotho perceive that they do not have any rights in South Africa, because of their illegal migrant status, though this is not true. [17] Since access to human rights is often tied up with citizenship, irregular migration status can be linked with a denial of various human rights. [18]

Additionally, gender factors heavily into the equation; women in general are paid less than men. [19] Women may have left their home countries due to gender inequality and discrimination, which increases the motivation for them to remain in their destination country and could create a situation in which they tolerate worse pay and more abuse than men would. [20] Furthermore, women in general receive less education than men, which can cause them more difficulties in accessing their rights and legal protections, again increasing their toleration of low pay and abuse. [21] And finally, women are much more vulnerable to sexual abuse than men, which could be perpetrated by their employer, thereby increasing inequality in the employer / employee relationship and decreasing their likelihood to advocate for better pay.

Finally, race also contributes to low pay for Black Africans. South Africa is a society with a long history of racial discrimination and violence, and though legally racial equality now exists, in reality Black Africans receive less pay than white, Asian, and coloured South Africans. On average, Black South Africans earn about 40% of the wages that white South Africans do. [22] In a country with high levels of wage differentials based on race, combined with migration status, Black undocumented migrants surely make less than their South African counterparts. Because of these overlapping systems of inequality and marginalisation, it is clear that targeting low pay as exclusively an employment sector issue is largely ineffective. Since labour rights are not the only cause of the low pay, increasing labour rights alone would not solve the issue.

Sources

[1] Altman, M. and Pannell, K. (2012) ‘Policy Gaps and Theory Gaps: Women And Migrant Domestic Labor’, Feminist Economics, 18(2), pp. 291–315. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2012.704149.

Wiego Law and Informality Project (2014) ‘Domestic Workers’ Laws and Legal Issues in South Africa’.

[2] Dinkelman, T. and Ranchhod, V. (2012) ‘Evidence on the impact of minimum wage laws in an informal sector: Domestic workers in South Africa’, Journal of Development Economics, 99(1), pp. 27–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.12.006, p. 29.

[3] Griffin, L. (2011) ‘Unravelling Rights: “Illegal” Migrant Domestic Workers in South Africa’, South African Review of Sociology, 42(2), pp. 83–101. doi: 10.1080/21528586.2011.582349, pp. 91-92.

[4] Bloch, A. (2010) ‘The Right to Rights?: Undocumented Migrants from Zimbabwe Living in South Africa’, Sociology. SAGE Publications Ltd, 44(2), pp. 233–250. doi: 10.1177/0038038509357209, p. 245.

[5] Altman and Pannell, 2012, p. 295.

[6] Griffin, 2011, p. 89.

[7] Griffin, 2011, pp. 86-87.

[8] Griffin, 2011, pp. 92-93.

[9] Griffin, 2011, p. 90.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Griffin, 2011, p. 83.

[12] Griffin, 2011, p. 86.

[13] Bloch, 2010, pp. 237-243.

[14] Nyamnjoh, F. B. (2013) Insiders and Outsiders: Citizenship and Xenophobia in Contemporary Southern Africa. Zed Books Ltd.

[15] Trad, S., Tsunga, A. and Rioufol, V. (2008) Surplus People? Undocumented and other vulnerable migrants in South Africa. Paris: Fédération internationale pour les droits humains, pp. 1–48. Available at: https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/za486a.pdf, pp. 29-30.

Bloch, 2010, p. 242.

[16] Griffin, 2011, pp. 86-87.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Bloch, 2010, pp. 238-239.

[19] Bloch, 2010, p. 242.

[20] Magidimisha, H. H. (2018) ‘Gender, Migration and Crisis in Southern Africa: Contestations and Tensions in the Informal Spaces and “Illegal Labour” Market’, in Crisis, Identity and Migration in Post-Colonial Southern Africa. Springer, Cham, pp. 75–88.

[21] Kawar, M. (2004) ‘Gender and migration: why are women more vulnerable?’, in Femmes Et Mouvement: Genre, Migrations Et Nouvelle Division International Du Travail. Geneva: Graduate Institute Publications, pp. 71–87.

[22] Pupwe, O. K. (2015) Three Essays on Racial Wage Differentials in South Africa. Western Michigan University. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1539&context=dissertations, p. 88.

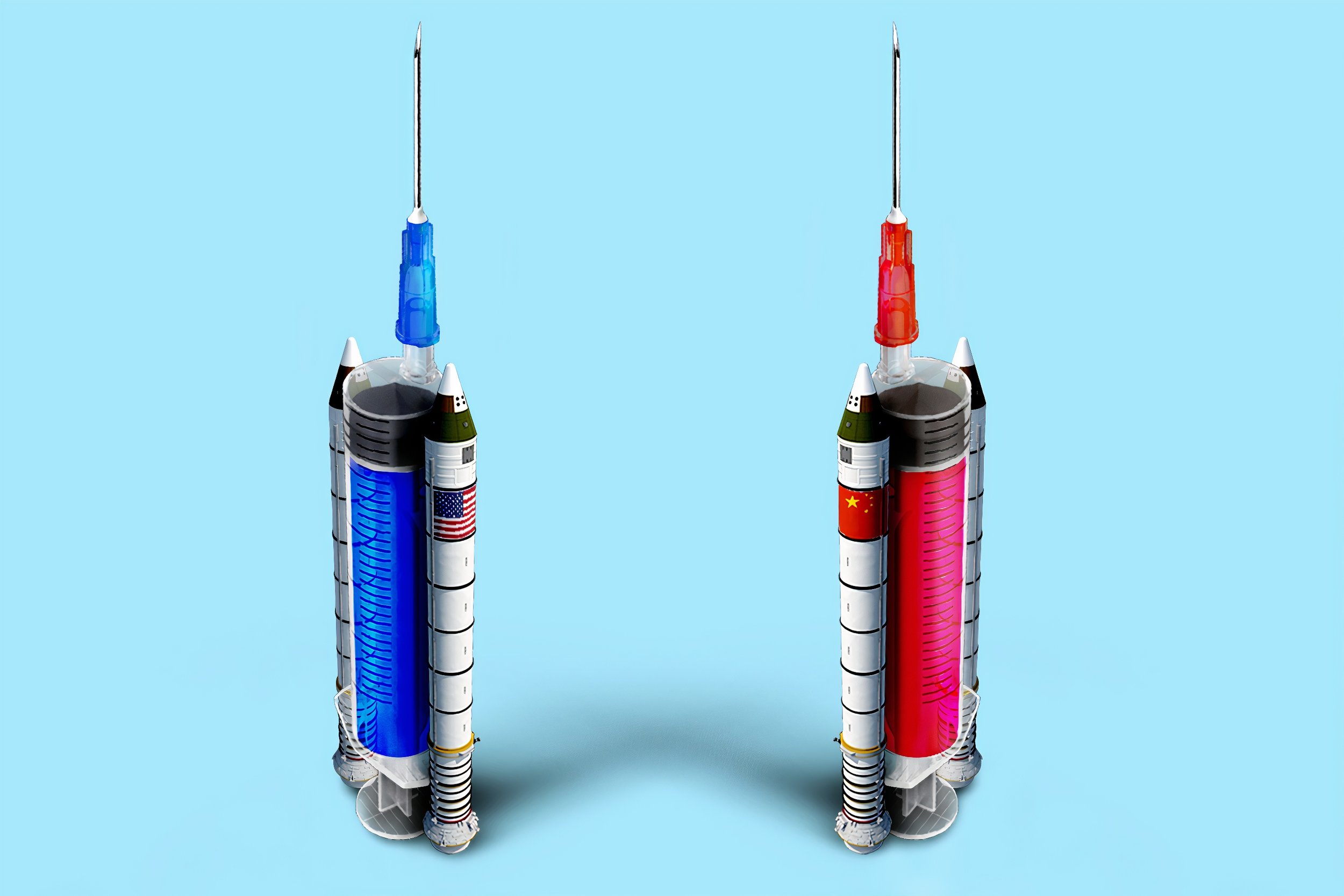

COVID-19 Pandemic Exacerbating Threats to Democracy

For this interview series, Fabiana Natale and Gilles de Valk are interviewing experts from different backgrounds on the political implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. From their living rooms in France and the Netherlands they will explore the consequences the pandemic will have for (geo)political, security, and societal affairs. This interview series marks the launch of a new type of content for the Security Distillery, one which we hope can provide entertaining and informative analysis of an uncertain and evolving development in global politics.

After seven episodes, we have produced a succinct analysis of the trends observed so far.

Download the brief here

The Hunt for Strategic Infrastructure: Geo-economics of China’s Territorial Ambitions

From an emerging to an established powerhouse in the region, China’s rise to power in Asia has been afforded by a series of strategic policies within a larger grand strategy, which has undermined central tenets of the Westphalian concept of sovereignty and territory. Through the revival of the Silk Road, China has acquired key infrastructure in Asia and Africa by leveraging weaknesses in international fiscal policies and lending programmes.

Conversing COVID – Part VII, with Francesco Trupia

For this interview series, Fabiana Natale and Gilles de Valk speak to experts from different backgrounds on the political implications of the COVID-19 pandemic in their respective fields. From their living rooms in France and The Netherlands, they will explore the (geo)political, security, and societal consequences of this pandemic. This interview series marks the launch of a new type of content for the Security Distillery, one which we hope can provide informative and entertaining analyses of an uncertain and evolving development in global politics.

The Realisation of China as an Emerging Global Power and Its Implications for Security

The existing world order mainly characterized by the triumph of Western liberalism is under threat with the emergence of new global power. The Asian great power, China is rising and ready to challenge the status quo. The United States (US) under Trump’s leadership is retreating from global leadership, while China is attempting to fill the power vacuum. China’s increasing strategic investment in international affairs and its commitment supports the argument that China is up for the challenge and serious about global leadership in playing the ‘responsible power’ role.

Can Tanzania be the Next Big LNG Exporter?

Energy export and production can be a source of political leverage for producers (America, Australia, Qatar) and a vulnerability for non-producing countries (the Baltic states) and developing energy producers (Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea). New energy entrants like Tanzania stand to benefit if resources are properly managed and invested. The recent discovery of over 46 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of offshore natural gas in Tanzania places the East African country as a significant competitor in the global Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) market. [1] Their proximity to the Asian LNG market heightens the expectation of this resource for power generation, regional supply, and intercontinental export. However, the political, legal, and security environment, along with the collapse in oil prices (to which most liquified gas exports are linked) and increased demand for cheaper and cleaner energy sources caused by COVID-19 all present challenges to Tanzania.

This paper will examine the political, legal, and security factors that may affect the viability of the new energy power, Tanzania, as a global competitor in the LNG market. Using secondary data, I observe an increasing level of repression in Tanzania, compounded with a failure to manage the expectations of job creation and social security. Therefore, LNG exploration could result in civil unrest and protests in Tanzania. Tanzania must therefore work twice as hard to attract and retain investors that will develop hard (roads, pipelines, railway) and soft infrastructure (capacity building, skilled labour, training) and establish legal frameworks that enable the people to have a stake in the resource.

By Ugo Igariwey Iduma

INTRODUCTION

The first offshore discovery of natural gas in Tanzania was made in 2010, which fuelled expectations of development and talks of its opportunities for the East African region and the continent overall. [2] Previous literature has focused on how the significant share of natural gas production can be used for power generation, transportation, and fertilizer production. [3] [4]. Recent studies, however, have failed to look at the structural, political, legal, and security factors that may affect new energy powers. Ernst and Young (2012) attempt to give an overall risk assessment of Tanzania. Yet, there is a need for an updated evaluation of the situation in Tanzania given the increasing rates of urbanization and the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak, which has forced millions of people to adapt to working from home, and therefore, increasing domestic energy consumption. [5] This paper runs a SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) of Tanzania and LNG exploration. A SWOT analysis will enable us to answer the question ‘Can Tanzania be the Next Global LNG Exporter?'

STRENGTHS AND OPPORTUNITIES

The high costs of generating electricity are causing Africans to demand further access to LNG because it is a relatively cheap, clean, and abundant source of energy. The large discoveries of LNG off the shore of Tanzania is expected to meet the rapidly growing worldwide energy demand, while also serving as an effective energy solution in East Africa. [6] Their proximity to India and South Asia instills optimism that if LNG plants are completed and production commences, Tanzania could be a significant LNG exporter. Being a significant exporter could lead to poverty reduction, job creation, and social security, creating the possibility of Tanzania climbing up the development ladder to middle-income status. [7]

THREATS

The increase of American unconventional gas production in 2006 coupled with the expansion of the Panama Canal in 2016, has caused the LNG market to become oversaturated and extremely competitive, [8] making it difficult for Tanzania to penetrate the market. In addition to their newness to the market, Tanzania must play catch-up to create relationships with foreign investors and secure buyers. Domestically, Tanzania struggles to secure financial investment to establish hard and soft infrastructures. COVID-19 has also made it increasingly challenging to keep existing investors, as the pandemic has caused foreign investors to retreat inwards to their home countries, causing a delay in plans to start LNG production. [9]

Infrastructure issues are compounded with the fiscal and regulatory uncertainties relating to taxation, domestic supply obligations, and local content requirements. [10] The 2013, Production Sharing Agreement Model (PSAM) local content policy requires firms to use domestically-manufactured and supplied goods and services is yet to be adopted effectively. Until the local content policies address the needs of the local communities, exploration and production (E&P), companies cannot begin production and expect a return on investment. [11] The stern local content requirements became a politically sensitive issue for Tanzania as violent protests broke out in 2013 over the construction of the Mtwara pipeline. Unless expectations are better managed, an LNG project could trigger similar unrest.

Additionally, the fall in oil prices in March 2020 also poses a risk to the commercialisation of LNG for Tanzania. LNG contracts remain heavily indexed to oil. With the development of export terminals at a high cost, lowering oil prices leaves the Tanzania LNG project at an estimated breakeven price of USD10.10 per million British thermal units (mmBtu) (excluding shipping). [12] In comparison to the United States (USD5.56 per mmBtu) and Australia (USD 3 per mmBtu) breakeven prices, Tanzania has to export its LNG at a higher price to make profits. [13] From these breakeven prices and oil prices dependency, Tanzania is put in an even more critical position in developing their LNG project.

WEAKNESS

Furthermore, the operational and legal constraints have forced Tanzania to prioritise domestic and regional markets over international counterparts. [14] Tanzania's domestic demand for natural gas is large, but the percentage of the population that can afford LNG energy is small. The problem becomes, can local people pay for electricity or will the government subsidise it? Government subsidies would not be sustainable economically if anchor industries (BG Group {Shell}, Equinor, Ophir Energy, Statoil and ExxonMobil) do not pay off the excesses allowing the government to subsidise the consumer. The commitment to payoff excesses is proven to be a loss for leading International Oil Companies in Tanzania, who are not short of alternative LNG projects to plough investment and expertise into as their focus is on sales and securing supply contracts. Shell and ExxonMobil, for instance, are both in the running to develop new Qatari trains and also have major North American projects lined up. Furthermore, Equinor lacks the capacity to pay off Tanzania LNG project without the support of other large players. [15] Their connectivity to other markets in the region also remains limited. LNG demand from neighbouring Burundi, Kenya, Congo, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe are low ( see table 1). [16] There are also limited opportunities for gas pipeline exports from Tanzania to neighbouring countries, for instance, Harare, Zimbabwe is 2,170.6 KM away from Tanzania (Mtwara) and Lusaka, Zambia is 1,982.0 KM from Mkuranga, Tanzania locations with drilling wells. Therefore, these high distances restrict options for export and investment without further infrastructure development.

Table 1: Natural Gas demand in East African countries

Source: [17]

From the table we see that power demand and generation are low in neighbouring countries such as Burundi, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Zimbabwe, with power consumption of less than 1bn KWh. Despite power consumption being less than 1bn KWh in 2019, demand for LNG specifically from Kenya is increasing at the rate of 3.6% annually representing an opportunity for Tanzania to become a regional exporter, but the potential is limited without substantial aid in the construction of gas pipelines in the destination market. [18]

Furthermore, the 1990s gold rush gave Tanzania a peripheral reputation of being exploited by foreign gold mining companies. As a result, much of Tanzania’s gold revenues accrued to gold corporations, while the needs of local people were neglected. In the eyes of ordinary Tanzanians, gas exploration is no different. Tanzania’s one-party system has cracked down on the media, civil society, and statistics, and the growing authoritarianism is breeding more organised opposition and lower confidence in government. This could result in protests or civil unrest particularly if the country does not peacefully reform to a multi-party system,, thus posing a risk to future investors and delaying LNG development. [19]

Under the current president John Magufuli, Tanzania has gone through a “mining revolution” that has left the President clashing with foreign mining corporations. In 2017 Magufuli accused foreign mining companies of theft and exploitation, fast-tracking three bills through parliament that included provisions of reviewing and annulling mining contracts that were under “unconscionable terms”. [20] Acacia Mining, the largest stakeholder in the Tanzanian gold sector – announced in 2017 that it was considering the full closure of its operations in the country so as to “protect our cash pile”. [21] Shock waves were sent not only through the gold, but also the gas sector, as the host government’s agreement to the construction of a gas terminal was still under negotiation at that time. These acts of political sniping have created delays in LNG production.

In conclusion, Tanzania’s threats and weakness include a lack of infrastructure, oversaturation of the global market, non-existent local content policies that include local communities, and increasing levels of authoritarianism. According to my analysis, these outweigh the strengths and opportunities of a large commercial resource deposit and proximity to lucrative Asian markets. Therefore, I deduce that Tanzania will not be a significant LNG exporter in its current situation. To overcome its weaknesses, Tanzania should design a "unitization initiative" with other East African LNG explorers (such as Kenya and Uganda) to pool their resources and market together to cut LNG production costs, gain access to hard and soft infrastructures, and greater competitiveness, while curbing construction time. As Tanzania’s gas sector focuses on regional and domestic LNG exports, it becomes important to pool the resources of other East African countries to construct their individual gas pipelines and terminals for Tanzanian LNG.

SOURCES

[1] British Petroleum (2016) BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

[2] Ledesma, D., (2013) East Africa gas–the potential for export. Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

[3] Foell, W., Pachauri, S., Spreng, D. and Zerriffi, H., (2011) 'Household cooking fuels and technologies in developing economies. Energy policy', 39(12), pp.7487-7496.

[4] Schlag, N. and Zuzarte, F. (2008) Market Barriers to Clean Cooking Fuels in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of Literature. Sweden.

[5] Denton F. (2020) Will COVID-19 leave fuel-rich African countries gasping for breath? International institute for environment and development. (online) Available from:https://www.iied.org/will-covid-19-leave-fuel-rich-african-countries-gasping-for-breath\

[6] International Energy Agency (2014) Medium-term Gas Market Report 2014: Market Analysis and Forecasts to 2019. International Energy Agency.

[7] US Energy Information Administration (2016) International Energy Outlook. Energy Information Administration (EIA), 2016.

[8] Leather, D.T., Bahadori, A., Nwaoha, C. and Wood, D.A., (2013) 'A review of Australia's natural gas resources and their exploitation. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 10, pp.68-88.

[9] Demierre, J., Bazilian, M., Carbajal, J., Sherpa, S. and Modi, V., (2015) 'Potential for regional use of East Africa's natural gas'. Applied energy, 143, pp.414-436.

[10] Boersma, T., Ebinger, C.K. and Greenley, H.L. (2015) An assessment of US natural gas exports. The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

[11] Sisa J. (2014) Local policies set back East Africa oil and gas projects. (online) Available from:https://globalriskinsights.com/2014/11/local-policies-may-set-back-e-africa-oil-gas-projects/

[12] Business monitoring institute (BMI) (2016) Tanzania oil and gas report: Includes 10-year forecast to 2025. Q4. BMI.

[13] Russell, C. (2020) Column: Asian LNG prices take bigger coronavirus hit than Brent crude. Reuter. (Online) Availiable from: https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-column-russell-lng-asia/column-asian-lng-prices-take-bigger-coronavirus-hit-than-brent-crude-idUKKCN2290YC#:~:text=Most%20Australian%20LNG%20projects%20are,to%20need%20slightly%20higher%20prices

[14] The United Republic of Tanzania (2013) The Natural Gas Policy of Tanzania., Dar es Salaam: October 2013, 14. Available from: http://www.tanzania.go.tz/egov_uploads/documents/Natural_Gas_Policy_-_Approved_sw.pdf.

[15] Petroleum Economist (2020) LNG spot trading continues to surge. (Online) available from: https://www.petroleum-economist.com/articles/midstream-downstream/lng/2020/lng-spot-trading-continues-to-surge

[16] Ledesma, p. 22

[17] Ibid, p.27

[18] International Energy Agency (2019) Kenya Energy Outlook: Analysis from Africa Energy Outlook 2019. International Energy Agency.

[19] Polus, A. and Tycholiz, W., (2019) 'David versus Goliath: Tanzania's Efforts to Stand Up to Foreign Gas Corporations'. Africa Spectrum, 54(1), pp.61-72

[20] The Parliament of Tanzania (2017) The Permanent Sovereignty Act, Part III. Printed by the Government Printer, Dar Es Salaam, 7 July 2017.

[21] Hume N (2017) Acacia warns of mine closure unless Tanzania lifts export ban. (online) Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/fe0a33b6-6e06-11e7-bfeb-33fe0c5b7eaa

Baltic Security: An Inward Look at Ethnic Tension in Estonia and its Threat to Democracy

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Estonia has been recognised as a leader of the Baltic states in their transition to becoming democratic powers. Estonia is often portrayed as a technological powerhouse; due to its Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre, Estonia plays a prominent role in Baltic regional security. Besides transitioning into an essential security position through technological advancement, the state also boasts the highest level of political participation from its citizens out of all post-Soviet states.[1] However, Estonian policies towards its Russian-speaking* minority creates a divide in the state’s population. With the COVID-19 pandemic wreaking havoc globally, one wonders how the virus will impact a state that struggles to include roughly a quarter of its population in civic participation. This article will explore the subject in detail, providing an analysis of Estonia’s policies as they relate to the country’s Russian-speaking minority, and the potential for COVID-19 to increase the rift between the Estonian population due to its economic impact on the state.

By Taylor Pehrson

Estonia gained independence on 20 August 1991 after 47 years of occupation by the Soviet Union. A fundamental objective of the 1992 Estonian Constitution is the perseverance of the ‘Estonian people, language and culture’. [2] This goal marks the sense of national pride the Estonian people had at the time of independence. However, it also set a precedent for a national division of those living in Estonia - a precedent that can be traced through the Constitution and various other Acts published in and after 1992. Through the nationalisation of Estonian verbiage, these documents markedly separate the country’s large Russian-speaking population.

After the Citizenship Act was enacted in 1992, 90% of ethnic-Estonians automatically became citizens while only 8-10% of non-Estonians gained citizenship. This is due to a law that granted citizenship to those who were living in Estonia before 1940, which was the year of Soviet annexation. [3] Because of the law, those that moved or were born in Estonia after 1940 during Soviet times had to apply for citizenship. New numbers show that ‘as of April 2012, 93,774 persons (6.9% of the population) remain stateless, while approximately 95,115 (7% of the population) have chosen Russian citizenship as an alternative to statelessness’. [4] Because many Russian-speakers have not been able to gain citizenship, this combined 13.9% of the population does not have the right to participate in Estonian democracy. Therefore, the question stands as to the legitimacy of Estonia’s democracy.

In order to provide answers, a thorough examination of Estonian citizenship policies and legislation is needed: How do they serve core democratic values, such as the civic participation of the whole population? Therefore, it is important to investigate Estonian elections and their impact on ethnic tension. Going further, this article will then analyse how the current global pandemic will impact both the strides the Estonian government has made since 1992 and how the virus could exacerbate ethnic divisions, particularly in relation to the Estonian economy.

Although Estonian policy has recently changed as a result of the state’s engagement with the EU and NATO regulations and standards, there is still a long way ahead before the gap between Estonian and Russian-speaking populations can be bridged. One of the main distinctions and roadblocks between the two populations is language. Within the Constitution, Language Act, Citizenship Act, Riigikogu Election Act, and numerous other government directives, language is a main feature.

The 1992 Constitution made speaking Estonian a requirement for gaining Estonian citizenship. Efforts to curb the language obstacle for gaining citizenship started in 1995, when the Language Act provided Estonian language courses for anyone taking the citizenship exam. [5] This included a government reimbursement program for the courses (provided one passes the exams), clarification that only a B1 level of proficiency is needed for citizenship, and the Department of Education providing language tutors for the courses. [6] Thus, language is dissipating as a barrier to citizenship in the state. However, due to the heavy influx of those applying for citizenship and limited state funding, this process is only slowly moving forward.

Language remains nonetheless a decisive barrier for anyone hoping to engage in civic participation in the state. As stated in the Language Act of 2011, ‘the language of public administration in state agencies and local government authorities is Estonian… [this] extend[s] to the majority of state-owned companies, foundations established by state and non-profit organizations with state participation’. [7] While the Act does make an exception for local governments in districts where half the population or more speaks another language, all other government operations must use Estonian and only Estonian. [8] This means that in order to be elected to any government position, a person must be fluent in Estonian.

Besides the Russian-speaking population not being represented in government positions, the right to vote and join political parties is also restricted. In order to vote in Estonia, one must be an Estonian citizen and 18 years of age. [9] Moreover, only Estonian citizens can join political parties. [10] Thus, because of the language barrier to citizenship that is only slowly easing, Russian-speaking people in Estonia who do not meet citizenship requirements are limited in their civic participation abilities. This means they may not vote or voice their opinions on matters relating to jobs and visas, issues that pertain particularly to the Russian-speaking population. A recently published study by the EU Marie Curie Research Training Network* found that ethnic-Estonians are twice as likely to vote in any municipal election than Russian-speakers. [11] While one could argue that Russian-speakers do not have an interest in civically engaging and thus their numbers are low, consideration of Russian-speakers’ limitations to participation should be acknowledged first to ensure the limitations do not prevent a significant portion of the population from participating.

If a large quantity of Russian-speakers are not able to vote or join political parties, or run for a government position, Estonia is losing out on the input of a significant portion of their population. It is no wonder that election season usually brings tensions to a boil. This became apparent in the Estonian parliamentary elections of 2019 when, two months before the elections, signs labeled ‘only Estonians here’ and ‘only Russians here’ were put up on different parts of Tram stops in Tallinn. [12] The action, done by a small political party, Eesti 200, ignited tensions in the capital that prompted the immediate removal of the signs and put Russian-speakers’ citizenship at the forefront of political debate. A small instance created waves of action and protest; one then wonders what the impact of a major event could have on the small Baltic state where tensions are waiting under the surface.

Estonia and the other Baltic states have fared well in the global COVID-19 pandemic in comparison with the rest of Europe, with trends of low numbers of cases and deaths. Part of the success may be due to Estonia’s societal emphasis on technology, as the transition to quarantine was rather seamless due to technological capabilities. [13] However, a large concern remains for both Estonians and the Russian-speaking population: the economy.

Because of the potential for an economic downturn caused by the pandemic, the Estonian Conservative Peoples Party with Mart Helme at the helm drafted a new bill in April. This bill would terminate the visas of unemployed workers from non-EU countries and expire long-term visas. [14] Helme commented on the bill, saying “in the current difficult time, when our own fellow country people are short of jobs and there are more people every day who have lost their jobs, we must support the residents of Estonia.” [15]

There has been a public outcry from the Russian-speaking community on the bill which would give more power to the employer to choose Estonian citizens over other workers. Because of the restrictions to Estonian citizenship and COVID-19, the process of citizenship has slowed dramatically; Russian-speakers now face deportation and the loss of visas due to the government attempting to provide Estonians with the jobs that are usually reserved for Russian-speakers. It is no wonder that in a poll taken in April 2020, 72% of the Russian-speaking population in Estonia was worried about the economic well-being of the state. [16]

However, other sources have implied that the pandemic has brought the Estonian population together. According to Dr. Tonis Saarts of Tallinn University, the pandemic has put prominent Russian-speakers, such as the chief medical officer of the Estonian Health Board, Dr. Arkadi Popov, at the forefront of the fight against COVID-19. [17] This has created a unifying image of the Russian-speakers and ethnic-Estonians coming together to defeat a common enemy. Alas, Saarts also comments that “the looming economic crisis will hit Russians harder than it will Estonians.” [18] Furthermore, due to the language division in the state, there is a distinct separation of Estonian versus Russian-speakers’ jobs, Russian-speakers being limited to mostly blue collar positions as they do not require knowledge of Estonian. Therefore, the pandemic’s unifying ability will soon be tested through the economy, as can be seen in the Estonian governments’ drafted bill to end certain visas.

Definitions of democracy, though all slightly different, all include civic engagement by the population as democracy’s cornerstone. In Estonia, the question of who qualifies as a citizen as well as language barriers prevent a portion of their population from civic engagement. With COVID-19 potentially destabilising the economy of the state, Russian-speakers now risk losing jobs and visas with little political representation in the matter. While the world slowly moves forward from the devastation the pandemic caused, a call to action in Estonia and other post-Soviet states is needed as the economy may override their work towards establishing democracy in the wake of the virus.

*The term Russian-speaker is used here to describe those that have Russian, Polish, Belarusian or other Eastern European background, but have lived in Estonia or were born in the state after 1940 (the year of Soviet occupation). Russian-speaker is used to replace the term ethnic-Russian since some migrants that entered Estonia during Soviet occupation were not ethnically Russian and instead, adopted Russian as the main language. This population is commonly grouped together under the term “Russian-speaking” in legislation, laws, and news sources in the Baltic region.

*The Integration of the European Second Generation Survey (TIES): this survey started in 2006 through a collaboration of research institutes in 11 European countries and Turkey. The survey sought to collect data on European second generation migrants. Within the Baltics, the survey measured the civic participation of different ethnic groups.

Sources

[1] Schulze, J. (2014) "The Ethnic Participation Gap: Comparing Second Generation Russian Youth and Estonian Youth", Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, 13(1) pp. 19-56. Available at: https://heinonline-org.ezproxy.lib.gla.ac.uk/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/jemie2014&id=19&collection=journals&index=journals/jemie (Accessed: 21 June 2020). p. 24.

[2] The Constitution of the Republic of Estonia 1992. Available at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/530102013003/consolide (Accessed: 28 June 2020). p. 1.

[3] Kirch, M. & Kirch, A. (1995) "Ethnic relations: Estonians and non-Estonians", Nationalities Papers, 23(1), pp. 43-59. Available at: http://tinyurl.com/qqzbx9k (Accessed: 6 March 2020). p 49.

[4] Schulze, J. (2014) "The Ethnic Participation Gap: Comparing Second Generation Russian Youth and Estonian Youth", Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, 13(1) pp. 19-56. Available at: https://heinonline-org.ezproxy.lib.gla.ac.uk/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/jemie2014&id=19&collection=journals&index=journals/jemie (Accessed: 21 June 2020). p. 26.

[5] Citizenship Act 1995. Available at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/512022015001/consolide (Accessed: 29 June 2020).

[6] Ibid.

[7] Language Act 2011. Available at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/506112013016/ (Accessed: 29 June 2020). p. 2.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Riigikogu Election Act 2002. Available at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/510032014001/consolide (Accessed: 30 June 2020). p. 1.

[10] The Constitution of the Republic of Estonia 1992. Available at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/530102013003/consolide (Accessed: 28 June 2020). p. 5.

[11] Schulze, J. (2014) "The Ethnic Participation Gap: Comparing Second Generation Russian Youth and Estonian Youth", Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, 13(1) pp. 19-56. Available at: https://heinonline-org.ezproxy.lib.gla.ac.uk/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/jemie2014&id=19&collection=journals&index=journals/jemie (Accessed: 21 June 2020). p. 35.

[12] Luxmoore, M. and Alliksaar, K. (2019) ‘”Only Estonians Here”: Outrage After Election Poster Campaign Singles Out Russian Minority”, RadioFreeLiberty, 10 January. Available at: https://www.rferl.org/a/estonia-election-posters-russian-minority-outrage/29702111.html (Accessed: 20 June 2020).

[13] Sander, G. F. (2020) ‘The pandemic has united us: A media divide fades in the Baltics’, Christian Science Monitor, Riga, 18 June. Available at: https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Europe/2020/0618/The-pandemic-has-united-us-A-media-divide-fades-in-the-Baltics (Accessed: 20 June 2020).

[14] Ed. Nomm, A. and Wright, H. (2020) ‘Interior ministry drafting bill to send unemployed foreign workers home’ ERR News, 1 April. Available at: https://news.err.ee/1071501/interior-ministry-drafting-bill-to-send-unemployed-foreign-workers-home (Accessed: 20 June 2020).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ed. Vahtla, A. (2020) ‘Poll Coronavirus awareness nearly equal among Estonian-, Russian-speakers’, ERR News, 5 April. Available at: https://news.err.ee/1072982/poll-coronavirus-awareness-nearly-equal-among-estonian-russian-speakers (Accessed: 20 June 2020).

[17] Sander, G. F. (2020) ‘The pandemic has united us: A media divide fades in the Baltics’, Christian Science Monitor, Riga, 18 June. Available at: https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Europe/2020/0618/The-pandemic-has-united-us-A-media-divide-fades-in-the-Baltics (Accessed: 20 June 2020).

[18] Ibid.

Doctors with dilemmas - Goma 1994-1995

Médecins Sans Frontières

This article is based on an interview with Rachel Kiddell-Monroe, who worked in Zaire and Rwanda with Médecins Sans Frontières Holland before, during and after the genocide against the Tutsis.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors without Borders.

When Rachel Kiddell-Monroe became Head of Mission for a drug distribution programme run by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in December 1993, she had been told this would be a quiet, peaceful posting in Goma, former Zaire, just across the border from Rwanda. At that time, no-one could have predicted that Goma would soon become the emergency refuge for over a million people fleeing a genocide in Rwanda. [1]

Back in 1993, Goma was not the international organisation hotspot it is today. MSF was among a few international organisations working on regular development projects and drug distribution programmes in the Kivu region. MSF France had been sending volunteers to Rwanda since 1982 [2] and other MSF sections had been present in the Great Lakes region since the early 1990s. [3] Yet, despite MSF’s presence in the region for over a decade, the organisation failed to properly understand the political context in which it was operating and thus the dynamics of the ensuing conflict and refugee crisis. [4] MSF was confronted with ethical dilemmas which challenged its role as an impartial aid organisation in the midst of a genocide.

The genocide against the Tutsis began on the 6th of April 1994 in Rwanda. At the same time, pogroms against Tutsis in the Zairean Masisi region had been intensifying. Rachel Kiddell-Monroe had been gathering information from locals and documenting the incidents against Zairean Tutsis and she alerted the MSF Holland headquarters in Amsterdam. As she recalls:

This is 1994. There is no internet, no facebook, no social media. There is no communication except through a satellite telephone and very, very limited possibilities to send something through a computer. That is really important to understand because it completely impacted the way we talked about, understood and responded to the genocide. [5]

The headquarters initially dismissed the nature and severity of the conflict, creating tensions between Amsterdam and the field team in Goma.

So when I talked to people in Amsterdam and told them that there was a genocide, they thought I was overreacting. It was really hard because there was a denialism going on in Amsterdam. And that caused delays within the organisation. [6]

The denialism or fatalistic attitude of humanitarian organisations towards the Rwandan conflict was rooted in a colonial mindset, and a tendency to explain African conflicts as ‘tribal wars’. [7] The MSF teams on the ground were preoccupied with the technical aspect of their work, providing medical aid and tending to the injured rather than focusing on the political climate in which they were working. MSF’s initial analysis of the conflict as an inter-ethnic conflict was based on a colonial historiography of Rwanda and thus failed to recognize it as a politically designed genocide. [8]

As the ongoing massacres in Rwanda intensified and the number of victims grew, MSF began preparing camps in the neighbouring countries for refugees to arrive from Rwanda. The MSF programmes in Zaire were placed under the direction of the emergency department and Rachel Kiddell-Monroe became the MSF Field Emergency Coordinator in Goma. However, according to Kiddell-Monroe the refugees did not come right away: ’What happened is that Rwanda was sealed off. People were kept inside. It was like a fishbowl: we could look in and see what was happening but we couldn’t get in and people couldn’t get out’. [9] The Rwandan military and militias were guarding the borders and preventing the Tutsis from leaving the country. [10] MSF could not evacuate Rwandan Tutsis over the border, not even their own local staff. [11]

Nonetheless, on May 11th, 1994, 30,000 Rwandans had reached Zaire. [12] That number increased to somewhere between 800,000 and 1,000,000 by mid-July [13]:

I don’t think it was ever contemplated that there was going to be this huge outpour [Sic] of refugees towards Goma. The understanding of Rwanda was that the Western side of the country tended to be more safe, less reactionary, with a strong society, whereas the Eastern side was much more fragile. It was believed that there would be a much bigger exodus of people in the East. That was some kind of understanding about Rwanda that proved to be false. [14]

As the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) advanced into Rwanda and the conflict intensified, many Rwandans fled to Zaire. Facilitated by the French military presence in the West, the defeated Hutu militiamen and génocidaires crossed the border among the refugees and reached the MSF Goma refugee camp. While the field team was aware that armed soldiers and perpetrators were among the refugees, the MSF Charter mandated them to remain non-partisan and treat everyone in their camp indiscriminately [15]:

Seeing people crossing the border, I could not see the difference between Tutsi and Hutu. There is no difference. I did not know who perpetrated and who was a victim. They all came across with nothing and desperate, so the only response from my team was to help those people. [16]

Once refugees settled in Goma and the camp became more established, leadership among the refugees began to form: the instigators and perpetrators of the genocide were gaining influence within the camp, notably taking leadership roles within the food distribution programme. Although the number of refugees in the camp was largely overestimated and the UNHCR delivered food and aid supplies accordingly, malnutrition was still affecting 10% of the refugee population in November 1994. [17] This was a clear sign that food supplies were not reaching the most vulnerable and that aid was being diverted by the militias present in the camp [18]:

There were team discussion about this. Some were saying that what we’re doing is being taken completely the wrong way. We tried to access women and children directly and put a focus on water and food supplies. But we weren’t the only NGO there and we were working with other organisations. The inter-agency work was complicated because some agencies did not believe there were any aid diversions. [19]

The security climate in the camp deteriorated and refugees willing to return to Rwanda were regularly threatened or killed by the militias. [20] Refugees suspected of being Tutsi or accused of being RPF spies were also killed by the militias, sometimes in front of MSF workers. [21] The defeated Hutu government spread fear among the Rwandan population using radio and urged the Rwandans to join the refugee camps, where the leaders of the genocide could expand their control and re-establish their power. [22] Essentially, the refugees became “hostages” of the militiamen in Zaire who were exploiting refugees as a human shield and benefiting from foreign aid to rebuild and strengthen their armed groups in order to attack the RPF forces in Rwanda.

The camps replicated a “mini-Rwanda” and perpetrators inside were infiltrating into the leadership of the camp. It was a million people camp, this was the size of Montreal, so there was a lot of space for leaders to take their place. That’s when we started to ask ourselves, should we really be here or not? [23]

MSF came to face multiple ethical dilemmas: should it continue its work in Goma even though its aid was being exploited by militias with the intention to pursue their genocidal goals? Or should MSF leave the camps, thus cutting the resources and aid supplies of the militias but at the same time depriving vulnerable populations in need? [24]

While there was a consensus among the different MSF sections that the current aid diversion by former génocidaires was unacceptable, opinions diverged on how to deal with the situation. Some sections believed staying in the camp was a form of humanitarian resistance to the perpetrators of the genocide. [25] Furthermore, their presence as an international NGO would enable them to witness and document what was happening in the region and continue to draw media attention to the cause. MSF France, on the contrary, was determined to pull out its programmes, and argued that diversion of aid was a violation of its fundamental principles and continuing their distribution of food and aid supplies to militias was a form of complicity. [26]

MSF Holland in Goma first requested the UN Security Council to deploy an international police force to protect the refugees from the perpetrators in the refugee camps, a request that was never fulfilled. [27] Advocacy through media and lobbying the international community to intervene were also strategies used by MSF. However, since the security situation was already precarious in Zaire, MSF was very careful with its public statements regarding the militias in the camps, to avoid putting their field staff in further danger. [28] Yet, the international community failed to intervene and by the end of 1995, all sections of MSF had withdrawn from the camps. [29]

The ethical dilemmas MSF was confronted with in the refugee camps shows that humanitarian aid is only effective when it is provided jointly with judicial and political action. [30] As a medical, non-partisan humanitarian organisation, MSF cannot and should not fulfill all these mandates. In times of armed conflict, population displacements and gross violations of human rights, humanitarian relief in the form of medical assistance, water supply, and food distribution is simply not enough. [31] The refugee crisis in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo proved that an international intervention would have been critical to prevent the militias from instrumentalising humanitarian aid with full impunity and pursuing their genocidal agenda. Yet, since the refugee crisis was solely treated as a humanitarian crisis, its political dimensions were ignored and the international community failed to intervene in time.

Sources

[1] UNHCR. (2000) ‘The State of the World’s Refugees 2000’, Chapter 10, p.246

[2] Bradol, J-H and Le Pape, M. (2017) ‘Humanitarian aid, genocide and mass killings, Médecins Sans Frontières, The Rwandan Experience, 1982-97’, Manchester University Press. 10

[3] MSF. (2014) ‘Genocide of Rwandan Tutsi 1994’, Speaking Out, p.11

[4] Bradol, J-H and Le Pape, M. 24

[5] The author’s interview with Rachel Kiddell Monroe on the 10th of June 2020

[6] Ibid.

[7] Stapleton, T. (2018) ‘Africa : War and Conflict in the Twentieth Century’, Routledge.

[8] Bradol, J-H and Le Pape, M. 24

[9] The author’s interview with Rachel Kiddell Monroe on the 10th of June 2020

[10] MSF. (2014) ‘Genocide of Rwandan Tutsi 1994’, 17

[11] Ibid. 16

[12] Ibid. 31

[13] Bradol, J-H and Le Pape, M. 47

[14] The author’s interview with Rachel Kiddell Monroe on the 10th of June 2020

[15] Bradol, J-H and Le Pape, M. 47

[16] The author’s interview with Rachel Kiddell Monroe on the 10th of June 2020

[17] MSF. (2014) ‘Rwandan Refugee Camps in Zaire and Tanzania, 1994-1995’, Speaking Out, 55

[18] Ibid. 32

[19] The author’s interview with Rachel Kiddell Monroe on the 10th of June 2020

[20] Bradol, J-H and Le Pape, M. 59

[21] MSF. (2014) ‘Rwandan Refugee Camps in Zaire and Tanzania, 1994-1995, 55

[22] Ibid. 28

[23] The author’s interview with Rachel Kiddell Monroe on the 10th of June 2020

[24] MSF. (2014) ‘Rwandan Refugee Camps in Zaire and Tanzania, 1994-1995’, 8

[25] Bradol, J-H and Le Pape, M. 62

[26] Ibid. 63

[27] Ibid. 8

[28] Bradol, J-H and Le Pape, M. 4

[29] Ibid. 4

[30] Ibid. 88

[31] Ibid. 91

Workshop series : Humanitarian Programme Development Workshop

In this first entry in the Security Distillery's workshop series, conducted by Ethan Pate, we have been focusing on programme development in humanitarian response. Dr Caitriona Dowd has led the workshop which introduced participants to the process of developing project proposals, seeking funding, and incorporate key aspects of design such as contextual analysis, needs assessments, and partnerships.

Organised crime in the Sahel, an inextricable puzzle?

For eight years now, we have heard about the Sahel as the theatre of a war on terror. Sparked in Mali with the Tuareg rebellion of 2012, the conflict, largely waged by jihadist organisations, quickly spread beyond the borders. Islamist groups have constantly been striving to expand their influence. They have built up their power by exploiting state weaknesses in the face of deeply rooted economic issues and socio-ethnic tensions already amplified by climate change. [1] However, a key ingredient of their success lies in the dangerous potential of organised crime and trafficking networks in the Sahel. This piece will first look at the criminal rings that have contributed to turning the Sahel into a powder keg, and for which the conflict has played a catalyzing effect. [2] Then, it will develop the argument that those trafficking practices nurture each other, which makes them even more arduous to overcome.

Overview of a region hustled by its criminal plurality

War and instability, combined with weak and corruptible states, have stirred the development of criminal trafficking routes and their overlap with terrorist networks. [3] Indeed, the Sahel, the boundary between Africa’s desert north and savannah south, and traditionally a land of passage with its caravan routes, is a valuable transit hub for licit and illicit trade today. Among the scourges that consume the Sahel, organised crime appears at the forefront, with its transnational trafficking networks. While a variety of illicit activities take place, migrant smuggling and trafficking in persons, arms, and drugs prove the most profitable. [4]

Migrant smugglers lead a very lucrative activity in a region with porous borders and severe violence. In the G5 Sahel countries (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mauritania, Mali, Niger) alone, the conflict has caused over 19,000 deaths. [5] With 2,000 attacks registered since 2012, [6] the armed efforts of jihadist groups led to the displacement of 900,000 people. [7] The addition of economic, political, and environmental concerns results in fluxes of over seven million international migrants per year, [8] creating great opportunities for smugglers. Exact figures are obviously hard to find due to the unlawful character of those activities, but the profit generated only through smuggling routes from the Sahel to Europe is estimated around $300 million per year, without mentioning considerable amounts of intra-regional migration. [9]

Furthermore, while migrant smuggling and human trafficking should be clearly distinguished from each other, they often end up being coupled as one issue. The purpose can differ depending on the population targeted. For instance, Nigerian women are the most common victims of sexual exploitation in Africa, [10] while men are mainly used for criminal activities or as workforce in fields and mines. Children, mostly coming from Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, have been victims of the sex industry. [11] However, in the last decade, there has been an unfortunate resurgence of the soldier children phenomenon, especially among terrorist groups. [12]

Regarding weapons circulating in the region, they mostly come from previous local conflicts or from arms trafficking. The most sought-after products are assault rifles and ammunition. [13] They can be sold or leased by corrupt members of security forces or imported from abroad. Since the Cold War, they were mostly issued in Warsaw Pact countries. However, since the outbreak of the conflict, Chinese-made weapons seem to dominate the market. [14] Eritrea and Djibouti, as the “African gateway”, play a key role in supplying arms to the Sahel. [15] More locally, the leading actors are terrorist groups.

Those organisations also play a central role in trafficking drugs. [16] It is not a recent development that literature on the involvement of terrorists in criminal activities is dominated by references to the drug trade. [17] The practice has a twofold purpose: it generates income, but can also weaken enemies through its addictive nature. [18] While non-state actors in West Africa have been playing a solely logistical role for years, providing a corridor from Latin America to Europe, the last decade has even allowed local drug production to appear in the Sahel. [19]

Complex nexuses between trafficking networks allow mutual consolidation

The major challenge is nonetheless the combination of all these criminal phenomena. They cannot be faced separately. Indeed, while Edmund Burke taught us that “slavery is a weed that grows on every soil”, certain soils might be more fertile – when shared with drug plantations for example. As a matter of fact, drug trafficking, with the addiction, financial issues, and community conflicts it causes, makes people more vulnerable to human trafficking. Additionally, it goes without saying that drugs, with their inhibitory effects, are valuable for people’s exploitation. [20]

On the other hand, trafficking in persons provides financial means, human resources, as well as networks for all sorts of criminal activities like weapons trafficking. An analysis of the organized crime index reveals a proportional evolution of arms and human trafficking in Africa and in the Sahel (cf. Appendix). [21] Weapons provide criminals with the necessary coercive power they need to subdue their human trafficking victims.

Besides, a dense and armed criminal network contributes to creating the proper environment to trigger violence and thus, exploit people’s weaknesses. Indeed, the growing black market in conventional weaponry has parallelled the escalation of violence in the region. [22] This relies in part on the supply available for rebel and terrorist groups, who disrupt an already unstable environment and further weaken national governments. They do so by damaging their territorial integrity, which hinders state-centric responses and allows a reinforcement of all the above-mentioned criminal phenomena. [23] Additionally, they induce financial losses by forcing the states to concentrate their efforts and resources on this asymmetric fight.

The direct outcome is thus the government’s failure to protect and provide for its citizens, leading to popular dissatisfaction. People can then deduce that they either need to provide for themselves – which can lead to an increase of the demand for light weapons – or to seek help from alternative groups. This is how the vacuum left by state authorities, if taken advantage of, can lead to considerable gain in legitimacy for criminal and terrorist organisations. [24]

These nexus are simply an illustration of how multiple aggravating factors can converge, leading to the vicious cycle for the Sahel security question. The region has been facing a diversity of geopolitical and humanitarian challenges that have not successfully been tackled despite five years of cooperation of local governments through the G5 Sahel, the French military intervention since 2013, and efforts of the international community. [25]

As shown, a major obstacle is the interconnection of multiple criminal activities which cannot be solved individually. Furthermore, a strictly regional response is not sufficient since the Sahel is not a closed-off area and constitutes a pivotal international hub for illicit markets and a central platform for drug trafficking [26]. Lastly, the financial fluxes and incomes generated by these trades cannot be ignored, especially in light of the role of the underground economy in Africa.

To conclude, in the last decade, the Sahel has been a puzzle of security challenges aggravated by humanitarian crises. As illustrated in this piece, the issues are deeply rooted and intertwined, which makes the bigger picture appear inextricable. Yet, the new decade began with further threats weighing in on the region: climate change and the coronavirus. On one side, the reduction in trafficking they caused is a reason to be hopeful. On the other, a more structured response is needed urgently, now that light has been shed on states in increasingly weak and precarious positions, therefore creating new opportunities for crime.

Appendix 1

Sources

[1] Le Monde Afrique (2020), ‘Comprendre la guerre au Sahel ( Les cartes du Monde Afrique, épisode 1)’ [online] Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j1tLiD6yjXM

[2] Enhancing Africa’s reponse to transnational organised crime (2019) ‘Organised Crime Index Africa 2019’ [online] Available from https://enact-africa.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/2019-09-24-oc-index-2019.pdf

[3] Ibid.

[4] US Aid, Bureau for Africa (2020), ‘Strengthening Rule of Law Approaches to Address Organized Crime Criminal Market Convergence’ [online] Available from https://globalinitiative.net/strengthening-rule-of-law-approaches-to-address-organized-crime-criminal-market-convergence/

[5] ACLED (2020), ‘The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project’ [online] Available from https://acleddata.com/dashboard/#/dashboard

[6] Ibid.

[7] Le Monde Afrique (2020), ‘Comprendre la guerre au Sahel ( Les cartes du Monde Afrique, épisode 1)’ [online] Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j1tLiD6yjXM

[8] Ibid.

[9] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2006), ‘Organized Crime and Irregular Migration from Africa to Europe’ [online] Available from https://sherloc.unodc.org/res/cld/bibliography/organized-crime-and-irregular-migration-from-africa-to-europe_html/Migration_Africa.pdf

[10] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2013) ‘Criminalité Transnationale Organisée en Afrique de l’Ouest : Une Evaluation des Menaces’ [online] Available from https://sherloc.unodc.org/res/cld/bibliography/2013/transnational_organized_crime_in_west_africa_a_threat_assessment_html/FRANCAIS_West_Africa_TOCTA_2013_FR.pdf

[11] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2006), ‘Organized Crime and Irregular Migration from Africa to Europe’ [online] Available from https://sherloc.unodc.org/res/cld/bibliography/organized-crime-and-irregular-migration-from-africa-to-europe_html/Migration_Africa.pdf

[12] RFI (2020), ‘Sahel: le chef de Barkhane alerte sur le recrutement d'enfants soldats par les jihadistes’ [online] Available from https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20200710-barkhane-bilan-inquietude-emploi-enfants-soldats-jihadiste

[13] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2013) ‘Criminalité Transnationale Organisée en Afrique de l’Ouest : Une Evaluation des Menaces’ [online] Available from https://sherloc.unodc.org/res/cld/bibliography/2013/transnational_organized_crime_in_west_africa_a_threat_assessment_html/FRANCAIS_West_Africa_TOCTA_2013_FR.pdf

[14] Ibid.

[15] Hansrod, Zeenat (2018) ‘Djibouti emerges as arms trafficking hub for Horn of Africa’ [online] Available from https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20180915-djibouti-emerges-arms-trafficking-hub-horn-africa

[16] Labrousse, Alan and Laniel Laurent (1999), ‘The world geopolitics of drugs’ Geopolitical Drug Watch [online] Available from https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/bfm%3A978-94-017-3505-6%2F1.pdf

[17] McCarthy, Deborah (2003) ‘Hearing Before the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate, Washington DC’

[18] Enhancing Africa’s reponse to transnational organised crime (2019) ‘Organised Crime Index Africa 2019’ [online] Available from https://enact-africa.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/2019-09-24-oc-index-2019.pdf

[19] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2013) ‘Criminalité Transnationale Organisée en Afrique de l’Ouest : Une Evaluation des Menaces’ [online] Available from https://sherloc.unodc.org/res/cld/bibliography/2013/transnational_organized_crime_in_west_africa_a_threat_assessment_html/FRANCAIS_West_Africa_TOCTA_2013_FR.pdf

[20] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2013) ‘Criminalité Transnationale Organisée en Afrique de l’Ouest : Une Evaluation des Menaces’ [online] Available from https://sherloc.unodc.org/res/cld/bibliography/2013/transnational_organized_crime_in_west_africa_a_threat_assessment_html/FRANCAIS_West_Africa_TOCTA_2013_FR.pdf

[21] Enhancing Africa’s reponse to transnational organised crime (2019) ‘Organised Crime Index Africa 2019’ [online] Available from https://enact-africa.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/2019-09-24-oc-index-2019.pdf

[22] Antoine, Jean-Charles (2015), ‘Trafic d’armes, l’étude des filières est une démarche majeure dans la compréhension des crises géopolitiques’ Diploweb [online] Available from https://www.diploweb.com/Trafic-d-armes-l-etude-des.html

[23] Enhancing Africa’s reponse to transnational organised crime (2019) ‘Organised Crime Index Africa 2019’ [online] Available from https://enact-africa.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/2019-09-24-oc-index-2019.pdf

[24] Natale, Fabiana and de Valk Gilles (2020), ‘Conversing COVID - Part II, with Mikel Irizar’ The Security Distillery [online] Available from https://thesecuritydistillery.org/all-articles/conversing-covid-part-ii

[25] Athénaïs Porret, Anastasia (2020) ‘Les déplacés du Sahel : une urgence humanitaire’ Les Yeux du Monde [online] Available from https://les-yeux-du-monde.fr/actualite/43802-les-deplaces-du-sahel-une-urgence-humanitaire

[26] US Aid, Bureau for Africa (2020), ‘Strengthening Rule of Law Approaches to Address Organized Crime Criminal Market Convergence’ [online] Available from https://globalinitiative.net/strengthening-rule-of-law-approaches-to-address-organized-crime-criminal-market-convergence/

Conversing COVID – Part VI, with Daniela Pisoiu

An Interview Series on the Political Implications of the Pandemic

By Fabiana Natale and Gilles de Valk

For this interview series, Fabiana Natale and Gilles de Valk speak to experts from different backgrounds on the political implications of the COVID-19 pandemic in their respective fields. From their living rooms in France and The Netherlands, they will explore the (geo)political, security, and societal consequences of this pandemic. This interview series marks the launch of a new type of content for the Security Distillery, one which we hope can provide informative and entertaining analyses of an uncertain and evolving development in global politics.

For this sixth episode, we interviewed Daniela Pisoiu, Senior Researcher at the Austrian Institute for International Affairs (OIIP) and expert of the Radicalisation Awareness Network. She has over fifteen years of experience in Islamist, right-wing and left-wing radicalisation, extremism, and terrorism, and is specialised in individual radicalisation processes. Her fieldwork includes interviews with (former) radicals and analyses of court files. In terms of regional focus, she works on Austria and Germany, as well as the Western Balkans and Europe more broadly. In our conversation, we first discussed radicalisation and deradicalisation mechanisms and then the exploitation of the pandemic by extremists.

Radicalisation is a gradual process and occurs in small steps. What is key when it comes to preventing it?

There are many important aspects, depending on who your target is and what stage one is at in the radicalisation process. To avoid this process from happening at all, however, an important concept to work with is critical thinking. Young people need to be provided with the capacity to use (social) media in a critical way, in order to resist indoctrination. If they do not, ideas can flow and evolve very quickly, especially due to the suggestion algorithms. Once you are in an environment where only similar ideas are propagated, it can be very difficult to get out of it.

You have interviewed returning foreign fighters for your research. How was it for you to talk with them about their experiences? And to what extent was it possible for you to understand their motives?

It is interesting and usually not so difficult. Sometimes I meet people who do not want to deal with what happened, they simply want to forget. Most of the time though, they do not have any problem with talking to me. However, some of them have their narratives already figured out for the trial and simply repeat it.

Not everyone believes what returning foreign fighters say, but I think it is true when they say they experienced a real shock and disappointment. They all left with that dream of a utopian, supportive, and just society, where children go to school and women can work. Then, they find out that those ideas are not implemented and they experience violence on a daily basis. They are disappointed with their comrades and the ideology, which is why they disengage.

As soon as they come back to Europe, they are thrown into prison. Some of them did not even regard themselves as criminals and never touched a weapon. However, according to the law, they are amongst the worst offenders as they are accused of terrorism. This is a huge psychological burden, on top of the sense of guilt some have towards their family and children. Of course, I am not saying they are victims, but we should invest more in this psychological and social aspect.

Nevertheless, there are also returning fighters who still strongly believe in the ideology of IS after coming back.

How is Europe currently dealing with returning foreign fighters and what could be improved?

Most European governments were and are not particularly eager to take people back because they fear they might lose support domestically. Besides, it is a very complicated process. There are more people coming back than are convicted, because it is not always possible to find evidence. Then there are cases of people who have already been in prisoner camps in Syria before coming back, which counts for their sentence once they are convicted in Europe. Therefore, if we wait too long to let them return, they will directly be free once they arrive. There are also debates regarding women, because some consider them as victims that have been lured, while others say they are responsible and might have taken part in the morality police in Syria. Finally, there are also divergences concerning children. In France, they are separated from their family straight away and receive psychological counselling. In Austria, authorities try to place them with other family members. Either way, those decisions are taken on a case-by-case basis. There is no standard procedure and no incentive to establish one.

In Kosovo, however, 110 individuals, mostly women and children, have been actively brought back by the government and there is an elaborate reintegration plan. Women are not put in prison and families receive support for education and social care. Kosovo is very advanced in this regard and other Western countries are now taking it as an example.

Given the depth of indoctrination of both returning foreign fighters and extremists who stayed in Europe, what are the keys of de-radicalisation?

The result of a de-radicalisation process has to do with the length and intensity of counselling. When a person radicalises, they enter a new world of ideas, and it takes time to reverse this; besides, accepting one’s own mistakes is difficult.

Social networks are usually considered as the key element in de-radicalisation, because one is indoctrinated and radicalised through other people. Therefore, changing the social environment of the person can help induce a change in their values.

Additionally, having an occupation is crucial. Being jobless is not a risk, but it creates opportunities, because you have more time to engage with radical ideas and people. Besides, occupations reflect factors such as self-esteem and the need to do something meaningful and this plays an important role, both in radicalisation and in de-radicalisation processes.

On top of that, the pandemic has led to a considerable increase in online activities. Did it also create new opportunities for radicalisation via propaganda on social media?

Internet plays a key role in radicalisation, because all kinds of information are available out there, even instructions on how to build a bomb. However, propaganda does not work on its own. Networks are even more important, because radicalisation is a social phenomenon and always happens with a feedback loop. Online, interactions simply happen at a higher speed and sometimes also intensity than offline, while the social and psychological process remains the same.

As internet and social media create more opportunities for propaganda and radicalisation, extremist groups obviously picked up on the increased online activities during the pandemic. This has been exploited by jihadis, presenting the coronavirus as a punishment of Allah for the West, by right-wing extremist movements denouncing a Jewish plot, and by individuals and groups promoting various conspiracy theories, which are the first step into indoctrination.

However, when analysing such mechanisms, it is essential to look at both the recruiting organisation and the people. On the one hand, there is the thriving offer by extremist organisations. On the other hand, there is the internet user who is sitting at home, isolated, eager to have meaningful interactions, and perhaps psychologically affected by the crisis. Indeed, those circumstances increase people’s vulnerability to believe in simple explanations.

Thus, I suspect that we will see a consistent increase of radicalisation, especially the right-wing kind. Furthermore, we might have a hard time countering those phenomena, since frontline fighters against online propaganda are chiefly not state authorities, but private companies such as Google or Facebook, with their content analysis algorithms and social scientists.

Not long after IS presented the pandemic as a punishment for the West, their occupied territories were affected by the virus. How did IS react to this? To what extent could they take advantage of the crisis?

Generally, as state authorities are trying to deal with the pandemic, they can allocate less resources in the fight against terrorist groups, which have the opportunity to flourish. IS reacted quickly as the virus reached them. They applied the measures suggested by the World Health Organisation, even though they were critical about closing mosques. In this sense, it is an opportunity for them to portray themselves as an actual state and to show what they are capable of. They want to prove they are better able to take care of the populations than local governments. Thus, they are able, yet again, to take advantage of unstable institutions and gain popularity against weak states, such as countries in the Sahel.

In that respect, terrorist and extremist groups are growing during the pandemic. Yet, we do not seem to focus on this issue as much as before the pandemic. Are we still well aware of the problem?

Media are currently paying less attention to terrorist and extremist groups, which is a good thing, since they live off publicity. Within specialist circles, I have not seen less care for those topics.

In recent years, IS has been putting less emphasis on the West. This is not due to the pandemic, but because they are increasingly focusing on regions such as the Sahel or Afghanistan. In Europe, we seem relieved about this shift, but it is important to understand that IS is not gone and sooner or later the consequences of their presence in other regions will affect us, too.

In the right-wing spectrum, we see an increase in activity and even attempts to weaponise the virus. We did not use to think of biological weapons as an asset that such organisations could manage, because of the medical and logistic skills it requires. However, this type of virus offers the opportunity for a significant individual empowerment. If used systematically and strategically, a simple cough can become a weapon and attempts have been already made in this regard.

While it is normal that states use their resources for other priorities at the moment, we have to remain aware of such risks and how they might evolve in the future.

What are the key takeaways from the pandemic regarding radicalisation and extremism?

In the Middle East and Africa, the pandemic can increase the importance of terrorism. We often underestimate this, because we tend to be Western-centric. In Europe, the crisis has accelerated the empowerment of right-wing radicals, which had already started in the last years, but has been largely ignored.