An Interview Series on the Political Implications of the Pandemic

By Fabiana Natale and Gilles de Valk

Over the summer of 2020, Fabiana Natale and Gilles de Valk conducted the ‘Conversing COVID’ interview series on the political implications of the pandemic. Now that many countries are experiencing another wave of infections and the world has learned more about the virus, Fabiana and Gilles are launching a second interview series: ‘COVID Continues’. They will speak to experts from different backgrounds on the (geo)political, security, and societal consequences of this pandemic.

For this first episode of our second interview series, we interviewed Jonáš Syrovátka, Program Manager at the Prague Security Studies Institute (PSSI). Mr. Syrovátka primarily works on projects concerning Russian influence activities in the Czech Republic. During our conversation we discussed the ‘infodemic’ amid the pandemic.

Can you tell us something about the Prague Security Studies Institute (PSSI) and the work you do?

PSSI was established in 2002, filling a gap in the field of security studies in the Czech Republic. Since then, it has developed as a prominent centre for security affairs, bringing together professionals and academics, and focusing on issues such as economic warfare and space- and cybersecurity. I started doing research at the Institute in late 2016, focusing on disinformation. I look at disinformation in elections, at disinformation business models of online platforms, and now also at disinformation throughout the pandemic, among other things.

The pandemic has led to an increase of online activity and a proliferation of disinformation. What are your most important observations regarding disinformation during the corona crisis?

It was interesting to see that people who are behind various conspiracy websites were actually surprised by the pandemic. They did not have a narrative at hand that they could start pushing, but soon enough they tried to incorporate this event into their broader agenda. Conspiracy websites tend to be critical about the West and the European Union in particular. Before the pandemic, for example, the EU would be criticised for migration issues, but now the handling of the coronavirus became their main point of criticism. Narratives about how the EU handled the pandemic fit into the broader narrative of the EU’s failures. I would say the coronavirus became a driver for such platforms, pushing their long-term agenda.

Who are the main actors of disinformation activities?

Disinformation in the Czech Republic is centred around dozens of websites, which are very diverse. People who are spreading disinformation are not only some mad men or proxies of foreign powers, but also entrepreneurs trying to benefit from people’s fear or longing for alternative explanations. So, there are ideological blogs, but also platforms that are trying to make money out of spreading conspiracy theories. Furthermore, these ideas are being shared on social media such as Facebook, so it is a very dynamic process. In a way, platforms are creating some kind of echo system that is interconnected.

In one of your reports on the ‘infodemic’, you made the distinction between different types of websites, such as ‘quasi-media platforms’, ‘conspiracy sites’, and the ‘blogosphere’. Could you explain their differences and why is it important to make these distinctions?

Quasi-media platforms attempt to present themselves as regular news outlets, providing some objective content, but a substantial part of their coverage is biased and problematic. Then there are conspiracy websites, producing outright lies and dubious theories. The third category is the blogosphere, where opinion pieces on fringe views circulate. They tend to mix some conspiracy thinking into their arguments. It is important to be aware of these distinctions when drafting strategies to counter those who are spreading disinformation and conspiracy theories.

Are there any distinct trends in what you called the ‘Czech disinformation ecosystem’ in one of your reports when compared to other countries?

Although I am not an expert on other countries, the Czech disinformation ecosystem is unique because it is also used by a Slovak audience. Czech conspiracy websites often have quite some follow-up in Slovakia. Czech disinformation and conspiracy websites often have quite some follow-up in Slovakia. For instance, this is significant for Russian news agency Sputnik, which has a Czech branch, but not a Slovakian one. Hence, the Czech website is supposed to serve the Slovak audience as well.

How has the response of the Czech government been so far in debunking disinformation narratives?

Initially, the response was good. Already in 2016, a National Security Audit was adopted, which focused on terrorism and migration, but also on disinformation. In 2017, the Centre Against Terrorism and Hybrid Threats was established by the Ministry of Interior. Furthermore, the Czech military made some great progress regarding communication in the past years. Unfortunately however, some developments halted because of a lack of political will, even though the plans on how to proceed are there. Still, the initiative seems to lie within the individual departments. It is not systemic enough and I think the communication problem of the Czech government has been made visible during the pandemic.

Conspiracy theories were considered harmless for a long time. Are we still underestimating their reach? And, are we dealing with them better than before?

I actually think we tend to overestimate their reach and influence in society at the moment, but we have to be careful and we need more research. In particular, we need more sociological studies on why people believe conspiracy theories and if or when people are willing to act upon them. Without this knowledge, we will not be able to reach out to these people and to return them back into the democratic discussion.

It seems like the coronavirus is here to stay for at least another couple of months. How do you think the spread of disinformation and conspiracy theories will develop over the course of, and after, the pandemic?

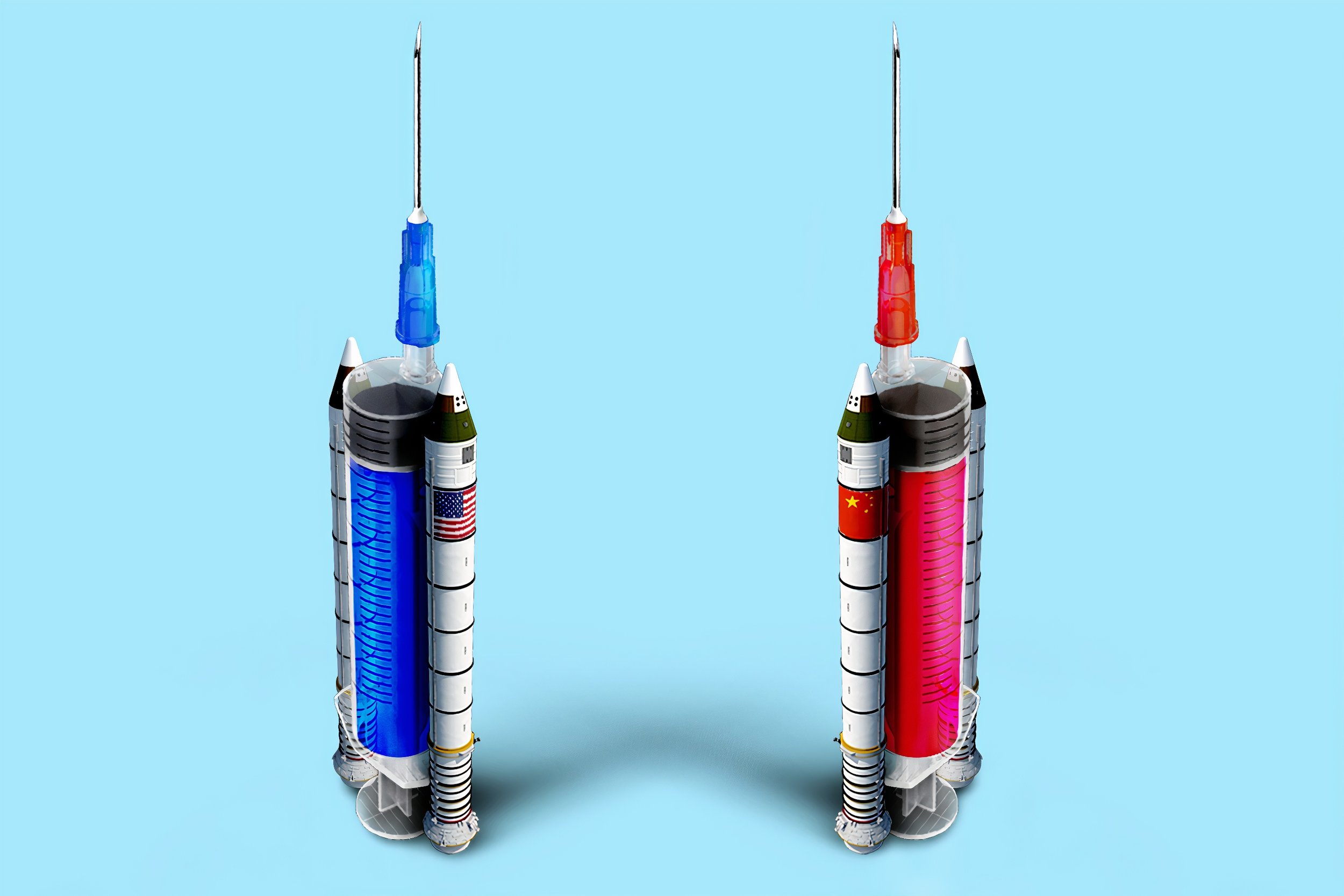

I think conspiracy theories will become more embedded in the everyday rhetoric. They will become especially dangerous when there are specific topics to interact with, such as a vaccine. This is an opportunity for engagement with pre-existing scepticism towards vaccination. I expect this to become an important topic. We will have to accept that after the pandemic, there will still be people who believe in conspiracy theories. However, this should be of no surprise, because we have had extremist politicians for the last thirty years, spreading dubious narratives. Nevertheless, the question is not whether conspiracy theories will stay or go, the question is how to limit their influence and how to make sure they will not lead to radicalisation and to people doing things that are really dangerous.

How closely affiliated are conspiracy theorists and rightwing extremists?

We should not underestimate the coalition between extremists and conspiracy theorists. Conspiracy theories provide a comfortable place for the buildup of an internal logic to support certain political positions, isolating them from the rest of the debate, which can be very dangerous. We should watch their engagement closely.

How can we counter disinformation?

There are multiple answers and we should realise countering disinformation is not only a security question, but also socio-political one. The crucial thing is to have a conversation about how the state should operate in the information space in the twenty-first century and how we can enforce laws in the online space. Secondly, breaking down advertising on disinformation websites by private parties could be an important step in limiting such websites’ outreach. On top of that, social media platforms should rethink their algorithms and how they approach their content. Nevertheless, I think the personal aspect is as important as the algorithms. Not only do we get information via social media, but also from friends, family, colleagues, and a number of other personal sources. Usually, we trust people around us the most, rather than Facebook.

What lessons should we learn from the pandemic?

The pandemic is a great case study for disinformation, because there is a set group of people in a set period of time focusing on a single topic. This helps us to better understand which actors are present in the information space and also to learn how to communicate with each other about our beliefs and opinions. 2020 is a terrible year to live in, but will be an interesting year to look back at.